The Foundations of Antisemitism

Unsettled times are often a breeding ground for increased antisemitism, and 1920s Germany was an example of this. The hatred of Jews that spread in Nazi Germany in the 1930s was based on ideas that had existed in Europe for a long time. The difference was the scale and how quickly a large part of the population accepted the persecution of Jews, as well as the tragic consequences it led to.

Swedish newspapers reported on the increasing persecutions but also on the Nazi ideology, where antisemitism was a core part from the start. Some Swedish journalists passed on the idea that the Jews were to blame for all the problems Germany had faced.

Header: Stockholms stadsmuseum.

Antisemitism in Sweden

In Sweden, antisemitism existed even before Jews lived here. As early as the Middle Ages, the Church spread anti-Jewish images and lies about the Jews. This was because the Church believed that the Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus.

In the 19th century, old antisemitism became linked with conspiracy theories about power and money. Antisemitism also took on racial biological elements. This was seen not only in caricatures in the satirical press but also in violent attacks on Jews. When Hitler came to power, antisemitism also increased in Sweden.

Interview with Börje Eliasson, USHMM and The Jewish Museum in Sweden.

Several well-known Swedish individuals were sympathetic to Germany. Among them was Sven Hedin, a Swedish explorer and author. He had close contact with several Nazi leaders, including Adolf Hitler. In an interview with Aftonbladet, he said:

I have studied the labour service, travelled on the new autobahns, and seen a Germany where everyone takes part in the work for the welfare of the state, a country where everyone works towards the same goal and where everyone has a job. It is the great miracle of these times.

About Sven Hedin (EN)

Sven Hedin was a Swedish explorer, author, and cultural figure who gained international fame through his travels, particularly in Asia. He was knighted and elected to the Swedish Academy. Hedin was politically engaged, expressed right-wing conservative views, advocated for a strong defence, and warned against the influence of communism.

He was also an outspoken supporter of Germany and expressed support for Nazi Germany. Hedin had close contacts with several Nazi leaders, including Adolf Hitler, and participated in various National Socialist organisations. He gave a speech at the opening of the Berlin Olympics in 1936 and spoke positively about developments in Germany. In an interview with Aftonbladet in December 1939, he commented on Nazi Germany:

"I have studied the labour service, travelled on the new motorways, and have seen a Germany where everyone participates in the work for the welfare of the state, a country where all work towards the same goal and where everyone has a job. That is the great miracle in these times."

His admiration for Germany and Hitler remained throughout the war. After Hitler’s suicide, Hedin wrote in Dagens Nyheter on 2 May 1945:

"I preserve a deep and indelible memory of Adolf Hitler and regard him as one of the greatest men in world history. Now he is dead. But his work shall live on."

Sven Hedin expressed a strong admiration for Germany, which was common among conservative circles in Sweden. He was a famous and influential figure, and his opinions and actions were harshly criticised in hindsight, overshadowing the fame and reputation he had gained through his expeditions.

Jews in Sweden early on had a clear picture of the persecutions in Nazi Germany. Many had family and friends on the continent and followed events through letters and Jewish newspapers. When the war broke out, anxiety and fear spread about what would happen in the event of a German invasion. Many Swedish Jews had packed suitcases, some carried weapons, and others had a poison pill with them, prepared in case the Germans invaded.

Antisemitism in Nazi Germany

After coming to power, the Nazis introduced hundreds of laws that took away the Jews’ freedoms and rights. The German Jews, who had lived side by side with other Germans, were separated from the rest of the population.

The Nazis saw the Jews as an inferior “race” while also considering them dangerous and a threat to the German people. According to the Nazis, the “Jew” was both the greedy capitalist and the violent communist. These contradictions are typical of antisemitism.

The war started by the Nazis was not only about gaining more land but also became a war of extermination against the Jews in Europe.

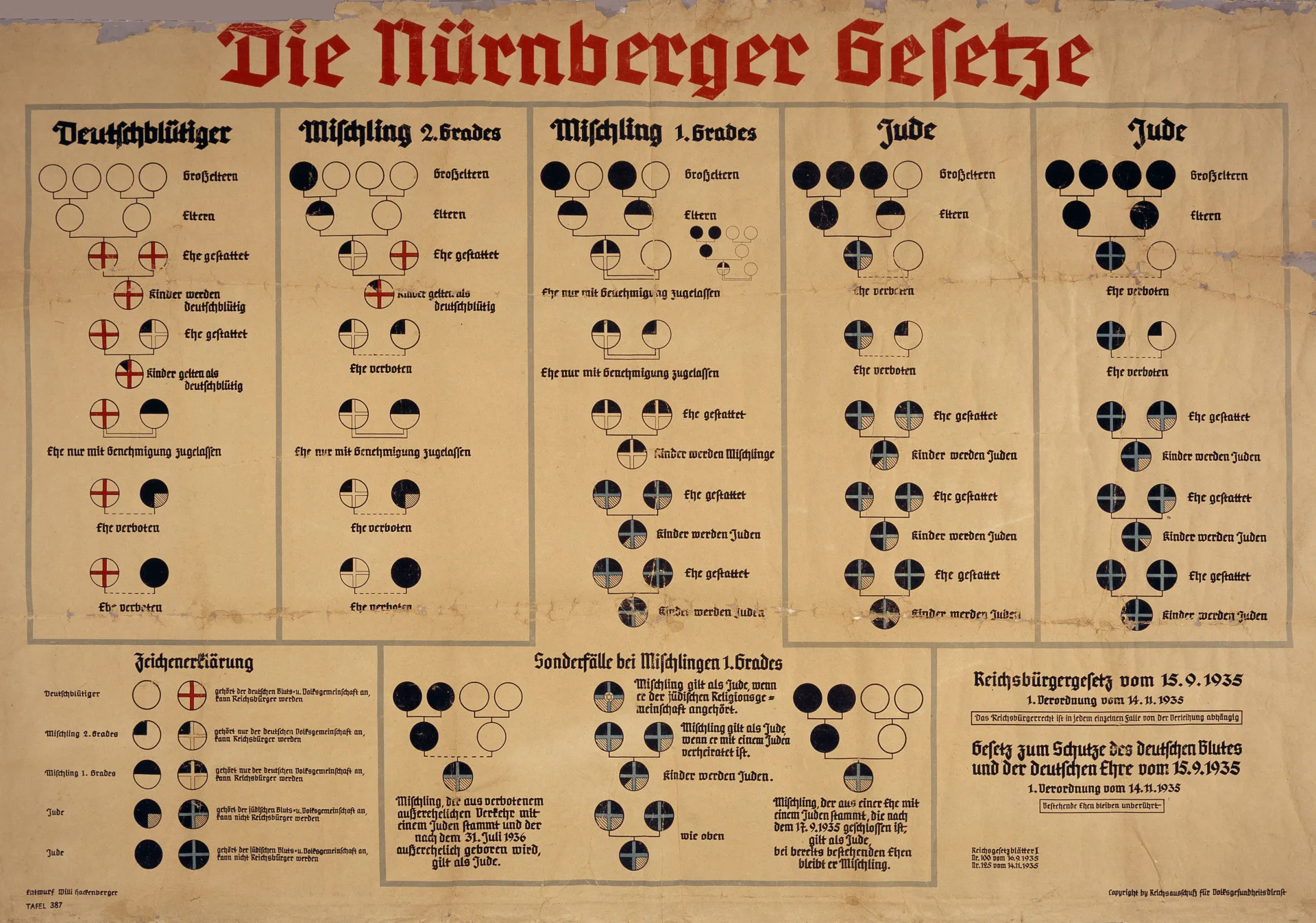

The Nuremberg Laws were some of the most significant laws introduced by the Nazis. The civil rights of the Jewish population were restricted, and marriages between Jewish citizens and “Aryan” citizens were banned. The schematic tables show how the law determined whether a person was considered a Jew or not.

Vad styrde pressens rapporteringar?

During the summer of 1942, Allied press began to spread reports about the Nazis’ mass murder of Europe’s Jewish population. The information came from the Polish resistance and had been smuggled out of Poland by Swedish businessmen, including Sven Norrman from the electrical engineering company ASEA.

Swedish newspapers were initially cautious about reporting the Allies’ information. This was partly because they were unsure about its accuracy and partly because they had government directives not to publish “detailed accounts of atrocities.”

Furthermore, the author Israel Holmgren had been prosecuted in the autumn of 1942 for including descriptions of Nazi crimes in his book Nazisthelvetet (“Nazi Hell”), and another book, Polens martyrium (“Poland’s Martyrdom”), had been confiscated on the orders of the Swedish Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson. Journalists therefore knew that the government did not want this information to be made public.

One of the first signs that the situation was changing was an article in Dagens Nyheter on 13 September 1942. It states:

The persecutions of the Jews have been extended by the Germans to the defeated countries, and by various signs it appears that the methods used have become increasingly harsh and ruthless. The final goal seems to be physical extermination.

Hugo Valentin wrote the first longer article about the mass murders in Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning on 13 October 1942. In the article, he also gave an estimate of the number of deaths at that time.

To what extent the Eastern European Jewish civilian population has been reduced through direct pogroms and mass executions is still difficult to determine. The statistical data is extremely incomplete and hard to access. According to the Information Minister, Mr Brendan Bracken (on 9 July 1942), the number of Polish Jews directly killed by the Nazis is estimated to be around 700,000, a figure whose accuracy has been disputed by the German side.

On 17 December 1942, Britain’s Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden read a declaration in Parliament in which the Allied nations condemned the Nazis’ mass murders. The declaration ended with all Members of Parliament standing for a minute’s silence. This public declaration marked a turning point in the reporting on the Nazi genocide.

Just a few days later, on 22 December 1942, the newspaper Arbetet wrote:

Last Thursday, the Polish Foreign Minister in London delivered a note to the Allied governments, stating that every day 7,000 Jews, men, women, and children, are being sent to special “extermination camps” established by the Germans in Poland. The note claims that Himmler, the German Nazi government’s Minister of Police, has given orders for half of the Jewish population in Poland to be exterminated before the end of December. The killings began already in the spring and have since been carried out with methodical thoroughness.

Hugo Valentin once again wrote a longer article about the mass murders in Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning on 31 December 1942, titled “The Greatest Jewish Pogrom in World History.” There, he reminded readers of what they could previously have read and understood:

There can be no doubt that such mass murders have for a long time been taking place systematically and on a large scale, and that every word in the [Allies’] carefully worded declaration corresponds to the truth. The opposite would, in fact, be surprising considering Hitler’s statements and promises. Time and again, ever since his major speech at the outbreak of the war, he has not only identified the Jews as the cause of the war but also declared his intention to exterminate them, at least in Europe.

From the turn of the year 1942/1943, Swedish newspapers published more and more articles describing the Nazis’ persecutions and crimes against the Jewish population in Europe. The newspaper Arbetaren even ran a report about Auschwitz as early as 25 October 1943, a year and three months before the camp was liberated by Soviet troops on 27 January 1945.

“In Oświęcim in Poland, the Germans have established a concentration camp which the local population has given the dreadful name ‘the death camp’. Christian Poles and Jews are brought there to either be murdered in large numbers or, as long as their strength lasts, to carry out various forced labour tasks for the German war administration. From a collection of reports published in London — from both credible observers and prisoners who have managed to escape — a brief description of the conditions in the camp is given here.”

Above the entrance gate to the concentration camp is an inscription in large letters: Arbeit macht frei! From all directions within the camp, one can see a tall chimney, similar to a large factory chimney. It is not a factory, but the chimney serves Oświęcim’s own crematorium. [---]