But the Swedish nurse’s sense of sterility was almost shattered. There we were, kneeling in the roadside dust, dressing the worst wounds and opening carbuncles.

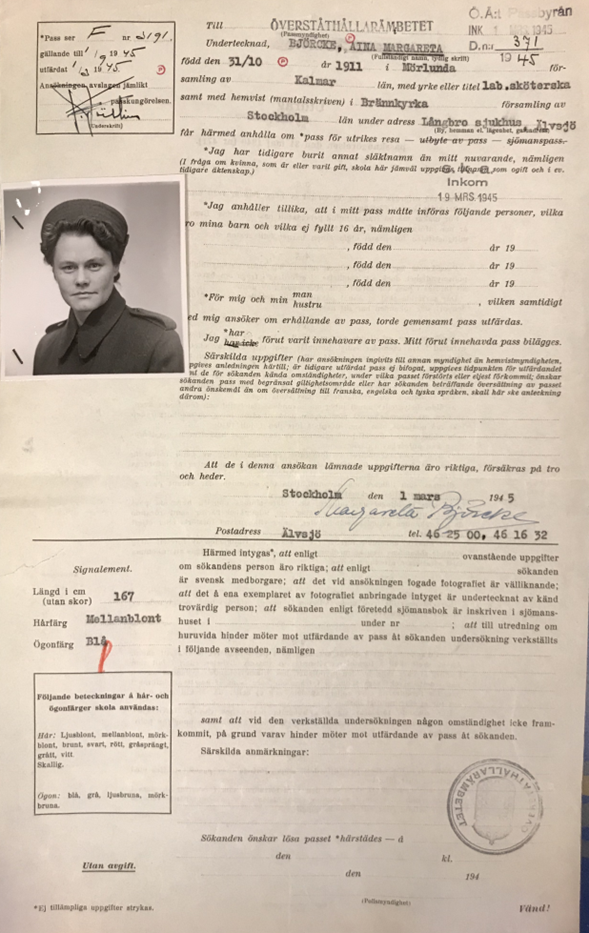

Margareta was born in 1911 in Mörlunda, Kalmar. Before joining the White Buses expedition, she worked at Långbro Hospital in Stockholm.

The White Buses Expedition

She talks about her first trip to Dachau. On the way down, they did not see much of the war as they drove on the autobahn. Allied bombers flew overhead, but they did not experience any shootings. In the evenings, they parked the buses under trees to hide them from the planes.

The return journey was nightmarish and an experience I will never forget. After loading the internees, it was clear that the convoy I belonged to had received most of the sickest people. In their malnourished, miserable condition, they were a pitiful group of people.

In the morning, we made our first stop after reaching the autobahn. Fortunately, the weather was nice, and as soon as we stopped, the buses emptied immediately — that is, everyone who could somehow get out threw themselves onto the grassy slope, took off their clothes to have their wounds rebandaged and receive help. In my twelve years of nursing, I had never seen so much suffering gathered in one place at one time.

Legs, backs, and necks were full of carbuncles (boils), so many that an ordinary Swede would be off sick for a week for just one — for example, on the neck. I counted about twenty on a single prisoner — and he still didn’t complain. By the way, I can mention that this man was later transported to Denmark, recognized me, came up, and thanked me for the help. He was then healthy, with a round face, shining with happiness to be free.

Most had clean dressings, often made of paper, but with a black tar ointment they hated. As soon as the bandages were removed, a little white ointment was applied, and the wounds were redressed with proper bandages, they were satisfied. The gratitude for even the smallest thing that flowed toward us is something one never forgets.

But the Swedish nurse’s sense of sterility was almost killed. There, kneeling in the roadside dust, we redressed the worst wounds and opened carbuncles. We had scissors and tweezers, which were roughly wiped with alcohol and sometimes briefly heated, but had to be used from one patient to another. We simply had no time or opportunity if we were to manage the absolute necessities. And the strange thing was that it apparently didn’t make the slightest difference. From eleven in the morning until late in the evening we worked — two doctors, two nurses, and one orderly.

We also had people lying with fevers of 40 degrees Celsius or more, and after consuming the contents of their care packages, nearly all suffered from diarrhea. It was terrible to see them sitting in long rows along the roadside. But they were so endlessly hungry. I saw them tearing open the packages and eating the powdered milk with spoons. What did it matter that half of it ended up everywhere but in their mouths? We warned them not to eat too much at once, but what good did that do? And we didn’t have the heart to take the packages away, even though we understood the trouble it would cause. But our supplies of opium and bismuth (a bacteria-killing powder) ran out quickly.

We drove all night, and early the following morning, the dressing rounds started again. Until three in the afternoon, when we delivered them at Neuengamme, we kept working. The last procedure the doctor performed was to open a wound behind an ear that stood out at a right angle because of the large amount of pus pouring out through the cut. Performing such an operation in an overcrowded, swaying bus at full speed was not easy. But not a word of complaint came from the man’s lips, and patiently he had waited. He only showed boundless gratitude that someone took care of him. The examples could be multiplied.

The Swede, who imagines a nurse as a strong woman dressed in white, would have been horrified by the trouser-clad, filthy figures climbing in and out of the buses, but here they were greeted with overwhelming warmth. And it was with sadness in our hearts that we saw the gates of yet another concentration camp close behind the poor human beings we had cared for during a few hectic hours.

Source: Excerpt from Sven Frykman’s book The Red Cross Expedition to Germany (1945), pp. 75–77.

Margareta stays

One of Margareta’s colleagues, Gösta Hallquist, was hit in the head by shrapnel during a bombing by English or American planes. He was in such bad condition that he couldn’t be taken home on one of the buses and needed immediate surgery. One of the Swedish doctors managed to convince a German doctor to perform brain surgery on Gösta to remove the shrapnel. The operation was successful, but Gösta was still too weak to travel home. Margareta chose to stay in war-torn Germany to care for Hallquist. She stayed for about a month and returned to Sweden on May 30th.

The Legacy

Margareta later painted two pictures inspired by the expedition. The paintings are owned by the White Buses Group within the Malmö branch of the Swedish Red Cross.