How did people get their news?

There were just over 230 newspapers in Sweden during the 1930s and 1940s. However, there was only one Swedish radio channel from 1924 until 1955.

The majority of newspapers were local or regional and focused on domestic news. Almost all daily newspapers were affiliated with a political party, which influenced their reporting. Larger daily and weekly newspapers had both the resources and the ambition to cover a wide range of topics, from international news to culture and entertainment.

Radio served as a unifying force in the nation, largely because the radio channel was state-controlled and Sweden had the highest number of radios per capita in all of Europe at the start of World War II.

Newspapers

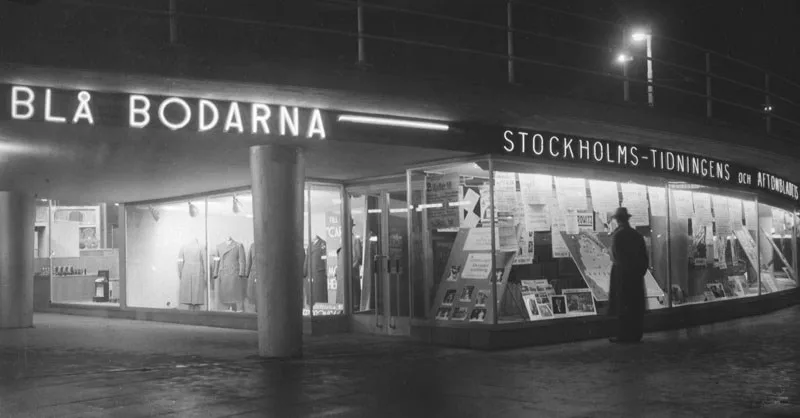

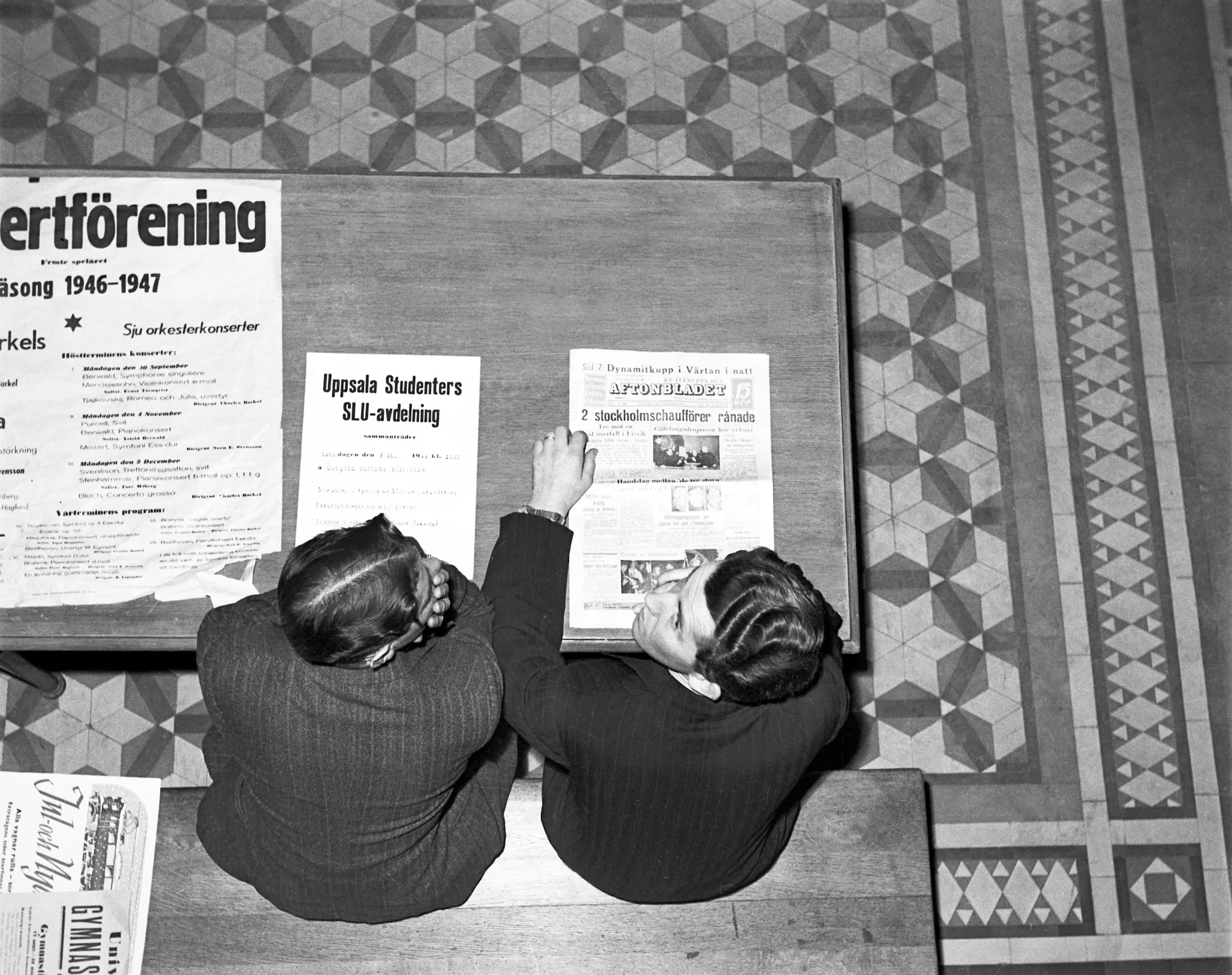

In a 1943 survey conducted by Swedish Gallup, the largest daily newspaper in the country was Dagens Nyheter, with about 10% of all adult readers. In Stockholm, as many as every second person read Dagens Nyheter. Among the evening papers, Aftonbladet was the largest until Expressen was launched in 1944.

Local and regional newspapers, however, played a more important role in smaller communities. Over 60% of the Swedish population read only local or regional newspapers. The reason was that readers found local news and advertisements more interesting than international events.

Sweden had two Jewish periodicals, Judisk Tidskrift and Judisk Krönika. These publications were an important source of information for both Jewish and non-Jewish readers, as they published articles about the worsening living conditions for Jews in Nazi Germany.

The major Nazi German newspapers, such as Völkischer Beobachter and Das Reich, were also available for sale in Sweden. They had few Swedish subscribers but were intensely read by Swedish journalists.

Swedish voices

Many of the news stories published in Swedish newspapers came from reports originating in the war-affected countries. Sometimes Swedish journalists were also on the ground. One of the journalists who was frequently at the center of these conflicts was Barbro Alving.

About Barbro, BANG, Alving (EN)

Barbro Alving, known by the pen name Bang, was a peace activist and journalist who wrote for Dagens Nyheter, where she made a name for herself and became synonymous with her signature "Bang".

Bang was known for her sharp wit and incisive writing. She did not hesitate to mock Nazism. For example, she wrote the following in Dagens Nyheter when reporting from the 1936 Berlin Olympics, where she was present:

"Deafened by clattering ‘Heil’ shouts, blinded by dazzling colours, and overwhelmed by the greatest celebration in modern sports history, I sit down to write this.

But now – fanfares sound outside, a steward's roar of ‘Sit down and fold up your umbrella’ echoes around the entire stadium, and 230,000 eyes are fixed on one single point. And then, in the wide eastern staircase, comes the brown figure with the well-known crook of the arm, followed by his grand retinue. A roaring ‘Heil’ sweeps over the stands, and the entire stadium becomes a giant hedgehog of outstretched arms."

"[…] There is no politics in these games, they have said, the high dignitaries. But there was certainly politics in the stands of the stadium during this half-hour. The cheering, the applause, the whistles, everything depends on one thing: Hitler salute or no Hitler salute. The raised arm is also an Olympic salute, I know that, but here it is Hitler’s."

Bang then described the atmosphere in the stands as various countries marched into the arena:

"When France’s large troop marches in wearing their blue berets and fraternally stretching out their arms in Germany’s own salute, the cheers rise to a storm, and when Austria’s 219 men do the same, the shouts grow into a full hurricane. […]

But in the Swedish team, only one arm is raised. It is a football player who has spotted someone he knows in the audience, and that greeting is Swedish. It means ‘hi’."

Bang continued to report from Europe and on Nazi Germany. She covered the Spanish Civil War, wrote war reports from the Finnish Winter War, and reported from Norway after Nazi Germany’s invasion in 1940. After the Second World War, she travelled to various refugee camps and wrote about the refugees' situation. Over time, she also became a highly popular columnist for Vecko-Journalen, writing under the signature "Käringen mot strömmen" (The Woman Against the Current).

Radio

Radio broadcasts in Sweden served largely as an information channel for the state. They also had a wide audience. The average Swede listened to the radio for two to three hours a day. News updates attracted the most listeners, especially during the war years.

Foreign broadcasts also had a significant following. About a third of Swedes tuned in to programs from nearby stations, such as Berlin or London. The BBC broadcasts from London were the most popular, followed by those from the Berlin transmitter. Music programs and news updates were of the greatest interest.

Swedes’ interest in foreign radio, combined with the warring nations’ desire to influence Swedish public opinion, led both the BBC in London and Reichsrundfunk in Berlin to air Swedish-language programs during the war.

News real

There were around 1,000 cinemas in Sweden during the 1930s and 1940s. A 1939 survey showed that people in Stockholm went to the cinema an average of 22 times per year. Between feature films, newsreels and advertisements were shown, this was the only way at the time to see moving images in advertising or news reporting.

By the 1930s, sound film had replaced silent film. However, all sound recording equipment was heavy, difficult to handle, and expensive. As a result, newsreels didn’t always include original sound, but they were always accompanied by a narrator’s voice.

Each film company decided which newsreels would be shown at its cinemas. Both the Swedish film industry and audiences preferred films from the United States and the United Kingdom over those from Germany. In response, the Nazi German film agency Tobisfilm opened a branch in Sweden, but it never achieved significant success.