Childhood

Inger was born in Oslo in 1923. Her mother died when Inger was 11 years old, so she grew up with her father and brother. Inger’s father worked in the fish markets, and the family was well off. He believed that women should also receive an education, so Inger was allowed to attend secondary school, where she, among other things, learned German.

Resistance

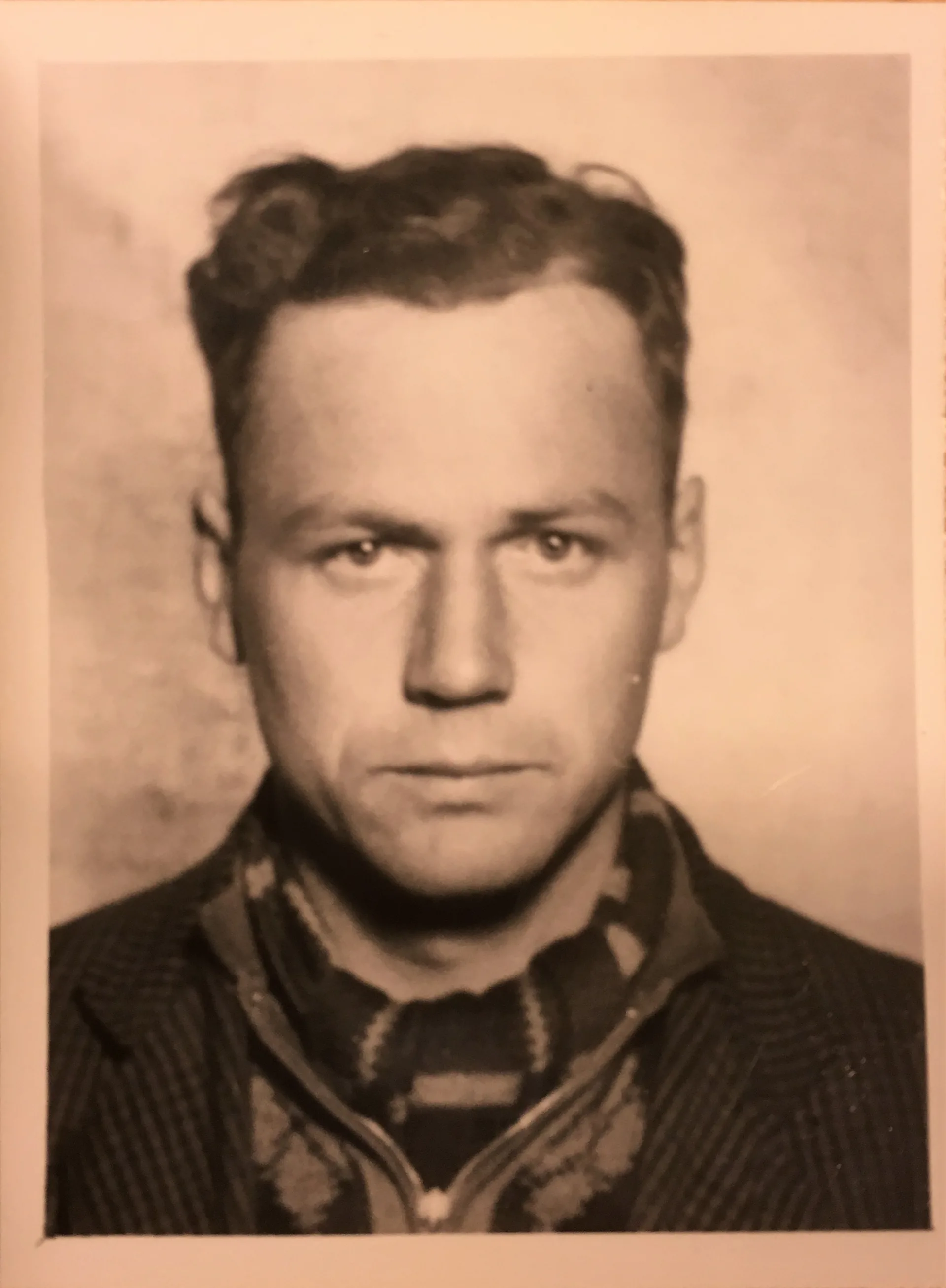

When Inger was 17 years old, the war reached Norway. She was a member of the labour movement’s youth organization, which also led her to join the resistance—alongside her father and brother. During World War II, Inger took part in underground resistance work. She smuggled information and weapons and passed on news to resistance movements in Germany, using secret messages hidden in everyday objects. She also helped rescue Jewish children by hiding them and bringing them to safety. During this time, she met her future husband, Olav Gulbrandsen. Their work was extremely dangerous, and eventually both were arrested by the Gestapo.

Concentration Camp

After their arrest, Inger and Olav were subjected to interrogations and imprisoned at Grini detention camp. From there, Inger was deported to Ravensbrück and Olav to Sachsenhausen—two separate concentration camps in Germany. The conditions in the camps were horrific, marked by extreme starvation, disease, and brutality. Prisoners were forced to work under inhumane circumstances, and Inger was made to carry out hard physical labour, such as road construction and transporting heavy materials.

Hygiene was nonexistent, and the camp was infested with fleas and lice. Food rations were minimal—often just a piece of bread and thin soup—which caused many inmates to quickly lose their physical strength.

Inger witnessed fellow prisoners dying from disease, malnutrition, or being systematically executed. She and the other Norwegian women stuck together and supported each other as best they could. They shared food, clothing, and words of encouragement to help keep hope alive. Inger was forced to take part in daily roll calls, where prisoners had to stand for hours in the cold and rain while the guards counted them. Sometimes she saw women and children being taken away to the gas chambers, knowing they would never return.

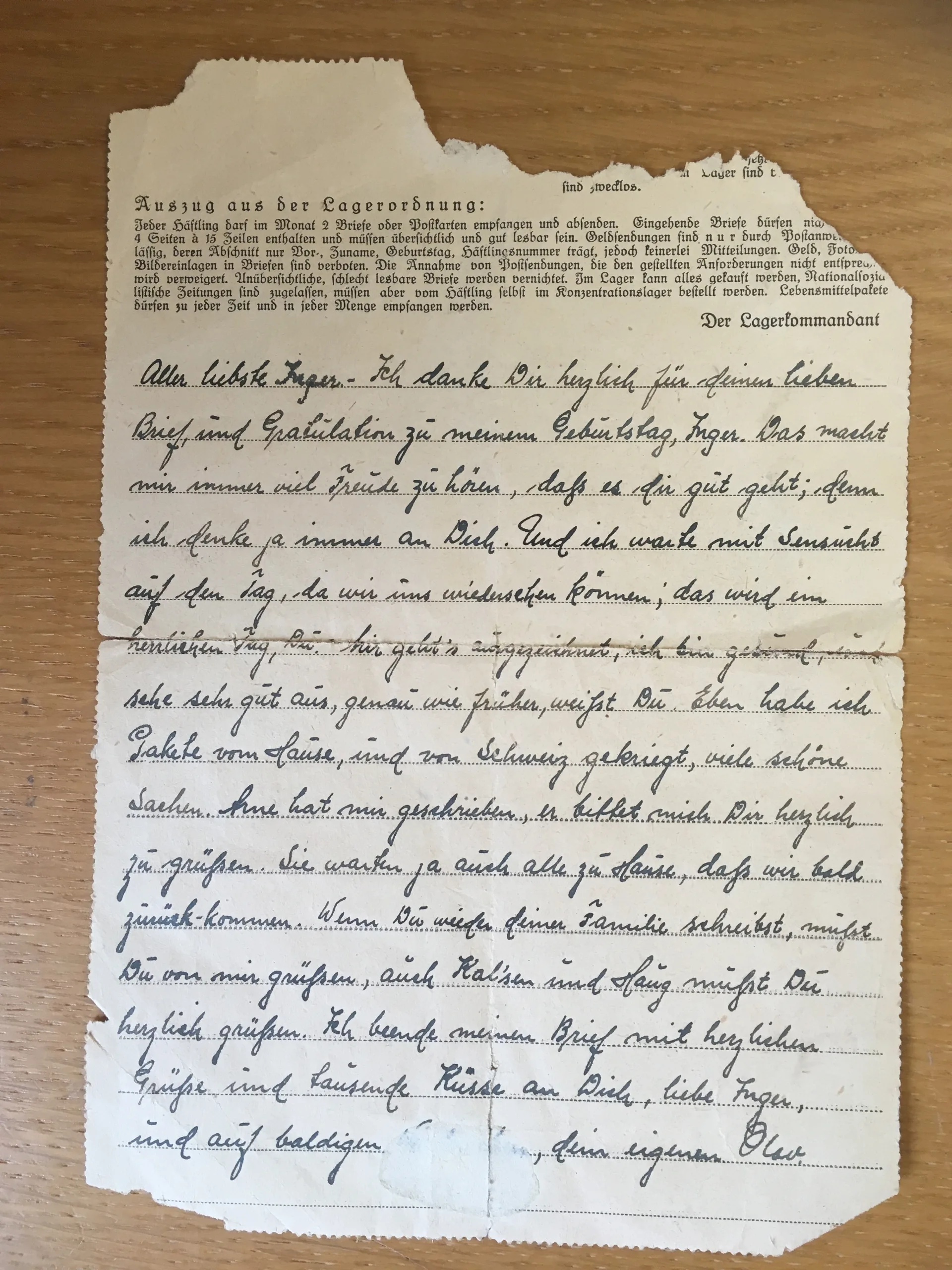

While in the camps, Inger and Olav were allowed to write letters to each other because they were classified as political prisoners. The letters had to be written in German to pass through camp censorship and had to be written on a specific type of form.

Transcription of the letter

The Rescue

The prisoners had lived in constant fear and starvation, and suddenly boarding a bus with white flags felt like a dream.

In April 1945, Inger was liberated along with other Norwegian and Danish women through the Swedish Red Cross operation known as the White Buses. She later described the experience of leaving the camp as surreal.

“The prisoners had lived under constant fear and starvation, and to suddenly step onto a bus marked with white flags felt like a dream.”

As they traveled through the bombed-out landscape of Germany, she saw the massive destruction and civilians searching for food and shelter among the ruins. This sight changed her perception of the German people—she realized that they, too, had suffered during the war.

Back to Norway

After the war, she returned to Norway, where she married Olav. Together, they rebuilt their lives, but the memories of the concentration camp never left her.

To process her experiences, Inger created miniature models of prisoners and daily life in the camps. These models are now on display at places including the Gamle Hvam Museum in Norway, in Aarhus, Denmark, and in Ravensbrück. She also became an active eyewitness, regularly traveling to Auschwitz with the White Buses Foundation to share her story and educate new generations about the horrors of Nazism.

Inger Gulbrandsen was awarded the King’s Medal of Merit in gold for her efforts and dedication to spreading awareness of the crimes of Nazism. She emphasized the importance of resisting oppression and ensuring that history is never forgotten.

Her words live on: “We must know what we are fighting against.”