Preparations

During World War II, many Scandinavian citizens—especially Norwegians and Danes—were deported and imprisoned by the Nazi regime. There were many reasons for this: some were Jewish, some held different political views, others were part of the resistance, and some were Danish border police. Many of them were sent to concentration camps and labor camps in Nazi Germany.

In 1944 and early 1945, people began to worry that these prisoners might be executed or die, as awareness of the terrible conditions in the camps increased.

In November 1944, N.C. Ditleff, a minister in Norway’s government-in-exile, presented a proposal to Sweden’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs. He suggested sending a Swedish Red Cross mission to Germany to rescue Scandinavian prisoners from various camps. The mission would take place while the war was still ongoing. The Swedish Red Cross then began negotiations with the Nazi regime.

Thanks to diplomatic efforts and support from the Swedish government, Count Folke Bernadotte—Vice President of the Swedish Red Cross—managed to reach an agreement with the Nazis. In January, after the negotiations, the first convoy with two camouflaged buses traveled to Germany to bring back Swedish-born women and children who wanted to return home. This was the beginning of what later became known as the White Buses mission.

The Operation

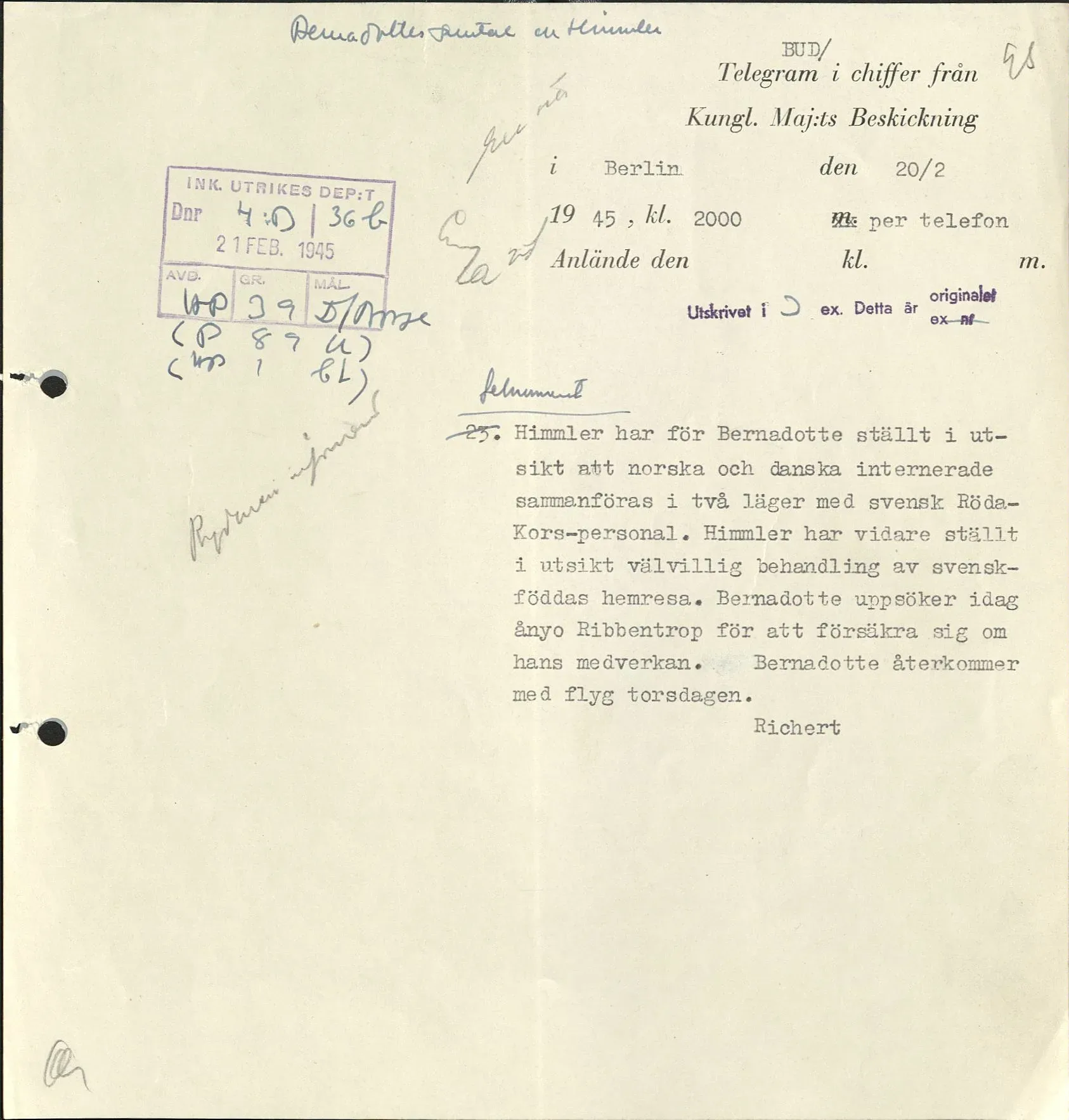

Folke Bernadotte continued his negotiations with Himmler, the head of the SS and responsible for the concentration camps. Himmler agreed to let a Swedish Red Cross mission pick up the Scandinavian prisoners from different camps and bring them together in the concentration camp Neuengamme.

The White Buses traveled from Sweden, through Denmark, and into northern Germany. It was a dangerous journey. The war was nearing its end, and the Allies were bombing German cities, vehicles, and roads.

The first destination in Germany was the concentration camp Neuengamme, outside Hamburg. Norwegian and Danish prisoners were gathered there to receive help returning home. Red Cross staff were also allowed to inspect the prisoners’ living conditions and provide medical care.

The Allies had been informed that the Swedish rescue mission used white buses with red crosses on them, but the message didn’t always get through. Air raids were common, and in many testimonies, passengers on the buses describe how they had to stop along the road and take cover in ditches or under trees.

Children, women, and elderly people were transported directly to Sweden, while other prisoners stayed at Neuengamme to receive food and care from the Red Cross.

After a while, German soldiers announced that Neuengamme was full and could not receive any more prisoners from other camps. The Germans demanded that the Swedes, using their buses and other vehicles, transport around 2,000 non-Scandinavian prisoners to other concentration camps. The Swedes reluctantly agreed to this condition.

Between March 27 and 29, about 2,000 French, Russian, and Polish prisoners were transported to camps in Hannover and Braunschweig. Each bus was escorted by two SS guards. Many of the prisoners were seriously ill, weak, or dying, and several died during the journey. In one bus, two prisoners were beaten to death by the German guards.

Driver Helge Andersson described how the Swedish drivers initially refused to move prisoners from one camp to another. But the Germans insisted that the transfer of Scandinavian prisoners could not continue unless space was made in Neuengamme. Orders from higher authorities told the Swedes to cooperate, and the transports began.

It was hardly an exaggeration to speak of walking skeletons with knobby arms, legs, and hands. Their faces were sunken, with eyes that were either extinguished or glowing with an animal-like fear, buried deep in their sockets and framed by dark circles. Their clothes were remnants of filthy rags—striped prison uniforms marked with a painted white cross on the back. Sleeves or pant legs were half-missing, or they had lost one or both entirely. Barefoot, or wearing a sock or shoe on only one foot. One long sock and one short.

The Operation Expands

The operation was originally planned to last only one month, so at the beginning of April, part of the team returned to Sweden. To extend the mission and help all the prisoners who were still left, Bernadotte accepted help from Denmark.

The operation expanded with both Danish vehicles and staff. In several groups, former concentration camp prisoners were transported through Germany to Denmark. On April 19, 1945, Himmler approved that all imprisoned Scandinavians could be brought to Sweden by the buses.

Norbert Masur, a German-Jewish businessman living in Sweden and sent by the World Jewish Congress, traveled to negotiate with Himmler. On April 21, Masur and Bernadotte succeeded in two separate meetings to arrange that all women in Ravensbrück would be handed over to the White Buses and the Red Cross. The negotiations took place during the night and morning of April 21. First, Masur was promised the release of 1,000 Jewish women. A few hours later, Bernadotte received permission to take as many people as he wanted, regardless of their origin, and to freely transport them to Sweden. Himmler understood that the war was over.

Both Swedish and Danish buses and ambulances were sent to Germany to collect as many former prisoners as possible and bring them to Padborg in Denmark. As the front lines approached, it became clear that the evacuation of Ravensbrück would not be completed in time, so the operation used trains to help. The first train arrived in Lübeck with 3,960 people, and shortly after, another train arrived with an additional 2,873 people. It was the commander of the women's prison in Hamburg who had sent women who had been held in camps around the city.

Arrival in Sweden

When the White Buses arrived in Copenhagen, they were greeted by cheering crowds. Many of the rescued people were taken to Sweden and first placed in quarantine. Some stayed in Malmö, while others were transported to different parts of the country.

Those rescued by the buses were called repatriates. The plan was to send them back to their home countries once they had recovered. War hospitals, internment camps, and other gathering places were set up for the repatriates around Sweden. You can read about some of the people who came with the White Buses in the Stories section.

The exact number of people saved is debated, as is how many of them were Jewish. Folke Bernadotte estimated the number of rescued people to be around 19,700. Today, after research, the Swedish Red Cross says it was about 15,000.

Many of those who worked on the White Buses later took part in a new rescue mission called the White Boats. Read more about the White Boats and some of the people who came to Sweden here.

What really happened?

The operation faced criticism already in 1945, but criticism has continued since then. The Red Cross’ mission was generally to help the most vulnerable, regardless of nationality or religion. In the case of the White Buses, the focus was mainly on saving Danes and Norwegians, who were often treated better than Jews and Eastern Europeans.

Critics argue that the rescue was guided more by the helpers’ priorities than by the real needs of the prisoners. Others point out that it would not have been possible to save anyone at all if Bernadotte had not first accepted Himmler’s demands regarding Scandinavians and later also agreed to move prisoners between different camps.