The city of Stettin where Hertha grew up was also home to her mother Hedwig and two of Hertha's sisters. Hedwig was retired but had worked as an English teacher before meeting Hertha's father Jakob. Hedwig's language skills meant that both Hertha and her sons spoke English as well as German.

In Stettin, Hertha and her husband Wilhelm ran a small hat factory. Interwar Stettin was a thriving port city, Germany's largest on the Baltic Sea. The city had a small but strong Jewish community of a few thousand people, of which the Heyman family was part of. Her husband Wilhelm was involved in the Jewish sports organisation Maccabi and served as secretary of the Stettiner Zionistische Vereinigung, the local Zionist association in the city. The family lived a religious Jewish life. They kept kosher, the children went to a Jewish school and the family often went to the beautiful synagogue in the city. They were well integrated into German society and lived together with both Jews and non-Jews.

Life for German Jews began to shatter when the National Socialists and Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933. In a short time, the country became a Nazi dictatorship. Jews were increasingly discriminated against and persecuted, which escalated over the years. Laws were introduced that quickly prohibited German Jews from serving in most public professions, such as doctors, teachers and lawyers. Jews were also excluded from various organisations and associations, such as sports clubs. The Nazis also banned kosher slaughter and the Heyman family, who kept kosher, abandoned meat products. Jews in the city were only allowed to sit on specific benches in the park. Youngest son Manfried, who was only four years old when the Nazis took power, later said that he had hardly any contact with non-Jews because they were afraid to make friends with Jews after the Nazi takeover.

Many Jews tried to leave Germany, which the Nazis encouraged. Wilhelm had managed to get permission for three family members to emigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine, but this would have meant that one of them would have to stay in Germany, so the plan was cancelled. Other family friends fled to Shanghai, but Wilhelm had no contacts there and probably couldn't afford to go. The family's financial situation had worsened because, like many other Jews, they had been forced to sell their shop in 1938 to 'Aryan' Germans, in what was called 'Aryanisation' – the transfer of Jewish property to non-Jewish ownership in Nazi Germany. Wilhelm was allowed to stay on for a short time while he mentored the new owner.

The synagogue in Stettin was burned down in 1938 during the November Pogrom, which lasted from November 7–13, but was most intense on the night between November 9–10. Wilhelm was one of more than 30,000 Jewish men arrested and sent to concentration camps during the November Pogrom. He ended up in Sachsenhausen where he stayed for two months before being released.

About the November Pogrom

The worst was not over, it had only just begun. With the outbreak of war, persecution increased as the Nazis began the genocide of Europe's Jews in areas they had conquered. In September 1941, Jews were forced to wear a yellow Star of David to distinguish themselves and shortly afterwards, Adolf Hitler decided that Germany's Jews would be deported to the east to die in ghettos, concentration camps, extermination camps or mass graves.

On the night between February 12–13, 1940, Hertha, her husband Wilhelm and their sons Eugen and Manfried were woken up by German soldiers and police officers. They were forced to quickly pack one suitcase per person and head to an assembly point in the city. There they met the rest of the city's Jews, including Hertha's sister and mother Hedwig. Hertha was 43 years old at the time and her sons were 16 and 10 years old. The Jews of Stettin were forced to leave their German money behind and instead were given Polish money and some food, before being loaded onto freezing cold trains to the city of Lublin in eastern Poland, a journey that took three to four days.

In Lublin, the family was put in a prison camp, from where they were sent to ghettos in various small villages in the neighbourhood. Hertha's sister was sent to the village of Głusk, while the Heyman family and Hedwig was sent to the small village of Bełżyce, where a ghetto had been established. The journey to Bełżyce was made on horse-drawn sledges in the deep snow. During the journey, little Manfried suffered from frostbite on his hands and feet. Hedwig, who was almost 80 years old, was so frostbitten that she died shortly after arriving in Bełżyce.

For the German Jews from Stettin, arrival in the Bełżyce ghetto was a shock. Many had lived prosperously and assimilated to life in Germany. Bełżyce had been a shtetl, a traditional Eastern Europe Jewish village, where most Jews were Orthodox and spoke Yiddish. The village consisted of half-timbered houses with no electricity or running water, unpaved streets and dry toilets in the courtyards. Despite the huge culture clash, the local Polish Jews helped the newly-deported German Jews. The Heyman family received help from a local Jewish shoemaker who lent them his farmhouse, which had a small room with two beds. Relations between the German Jews and the Polish Jews were difficult due to both language barriers and major cultural differences.

Many of the Jews in the small ghetto were forced into various forms of slave labour in the area. The Nazis constantly terrorised the ghetto's inhabitants with raids and arrests, leading to deportation to slave labour or concentration camps. In the summer of 1942, the Germans began 'liquidating' or emptying the ghetto. The local Jewish council, the Judenrat, had learnt that the entire ghetto would be 'relocated' and many of the Jews, including the Heyman family, hid in the attic of a house. The Nazis, assisted by militiamen from neighbouring Ukraine, began searching the entire ghetto.

In hiding, the family could hear the screams and the sound of gunfire. When all was quiet, they ventured out of their hiding place along with other Jews who had managed to hide. They were greeted by a terrible sight. In the streets and houses, children, the elderly and sick lay murdered. Other arrested Jews had been forced onto trains that would take them to the Majdanek extermination camp and almost certain death, while their property was looted. Those who hid and survived were now forced to bury the dead.

Shortly afterwards, a man arrived in the ghetto who had managed to escape from the Sobibór extermination camp. Tens of thousands of Jews had already been murdered in the camp since it opened in May 1942. He started telling the inhabitants about everything that happened there. About the "showers", which were actually gas chambers, and the fact that the only Jews who survived there were those who were forced to bury the dead and sort the belongings of the dead, the so-called Sonderkommando. The residents refused to believe the man's testimony, and someone quickly turned him in to the Gestapo, who took the man out of the ghetto and shot him. But when the Jews sent to bury him saw that he was still alive, they smuggled the man to the ghetto doctor, who saved him. What happened to the man afterwards is unknown.

From ghetto to camp

The ghetto was subject to another raid by the Germans. Of the 500 people arrested, 200 were selected for work, while the rest was murdered. Hertha's husband Wilhelm managed to persuade one of the German officers, who was friendly to German Jews, to allow their young son Manfried to survive and work. Hertha, her husband and sons were sent to a camp in Budzyń, near Kraśnik, which was a satellite camp of the larger Majdanek concentration camp. There, Hertha was forced to work as a maid in the barracks and was sometimes fed by the soldiers. Her son Manfried found work as a blacksmith, while her husband Wilhelm and older son Eugen worked in an aeroplane factory. The camp's commandant was a terribly brutal man, sometimes shooting prisoners from his window if they stopped working, even for a second. In the camp, people were shot and whipped for anything.

The Heyman family was transferred from the camp in Budzyń to the Mielec camp outside Krakow, which was a satellite camp of the infamous Kraków-Płaszów camp. It was also an aircraft factory and the family was subjected to slave labour in various ways, both in the camp and factory. Each month they were treated for lice since the Germans feared an outbreak of typhus. The family had miraculously managed to stay together but was now being torn apart. Russian forces were approaching and the Germans began evacuating prisoners westwards.

In spring of 1944, Hertha's husband and sons were transported from Mielec on the long journey to the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria, Germany. Flossenbürg was not only a camp for Jews but also for other members of German society 'unwanted' by the Nazis - Jehovah's Witnesses, homosexuals and prisoners of war. In Flossenbürg, Hertha's husband Wilhelm was forced to work in the quarries and died in November 1944. Older son Eugen was deported from the camp in February 1945 and died of starvation.

Hertha remained in Mielec for a short time until she was sent to the main camp in Kraków-Płaszów. She worked in the office as a typist but was soon taken to Auschwitz. Hertha was given prisoner number A-23286, which was tattooed on her left forearm. In Auschwitz, she took care of two sisters from Szczecin who had been with her all the way from Bełżyce. On arrival in Auschwitz, Hertha and the older sister passed the selection but the younger sister did not. The older sister still chose to go with her younger sister and both were probably murdered in the Auschwitz gas chamber.

Hertha remained in Auschwitz for three months before being taken to Bergen-Belsen. In the overcrowded and disorganised camp, diseases such as dysentery, diphtheria, typhus, and tuberculosis spread and killed thousands. Hertha became infected with tuberculosis.

Liberation and time in Sweden

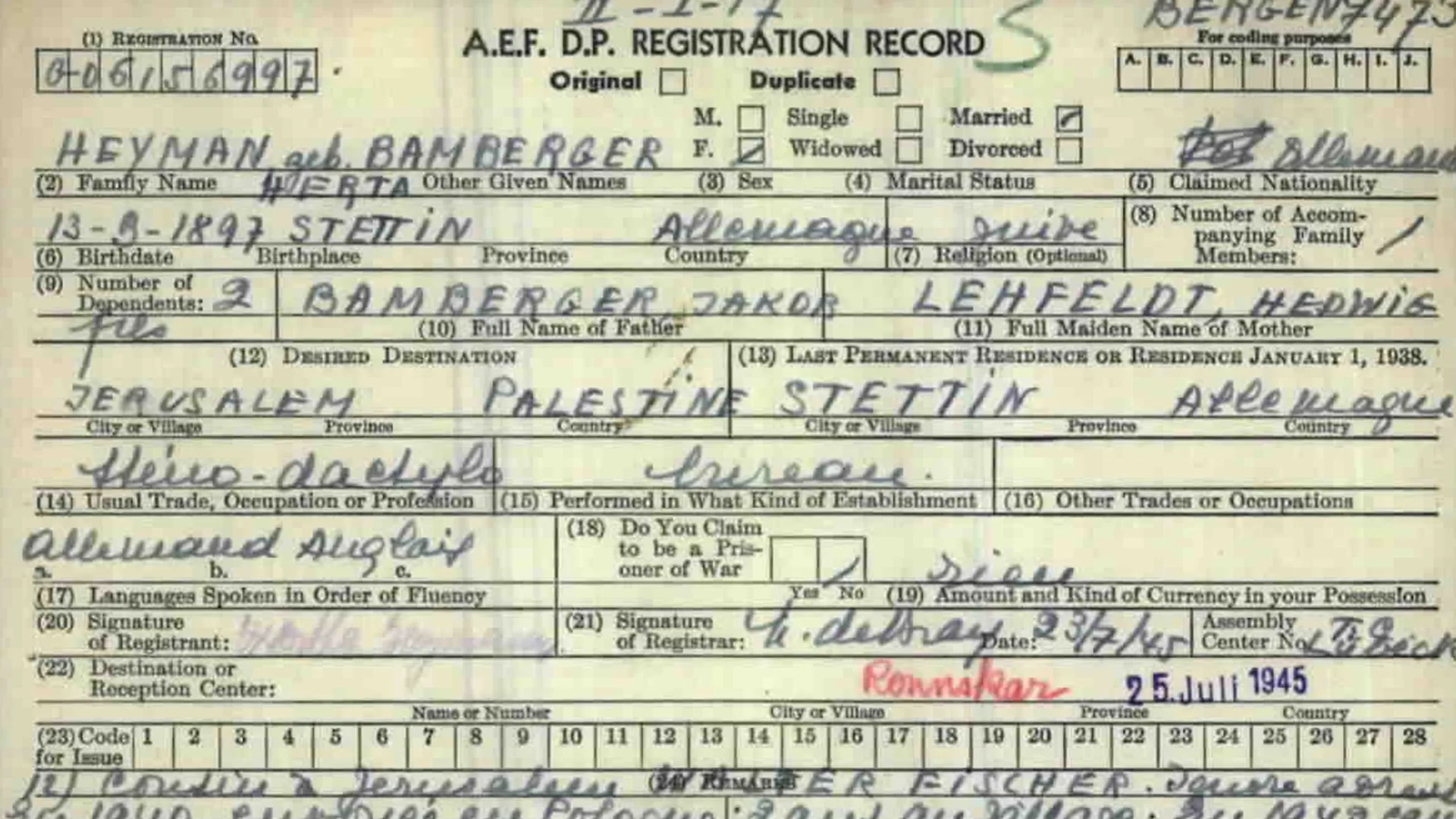

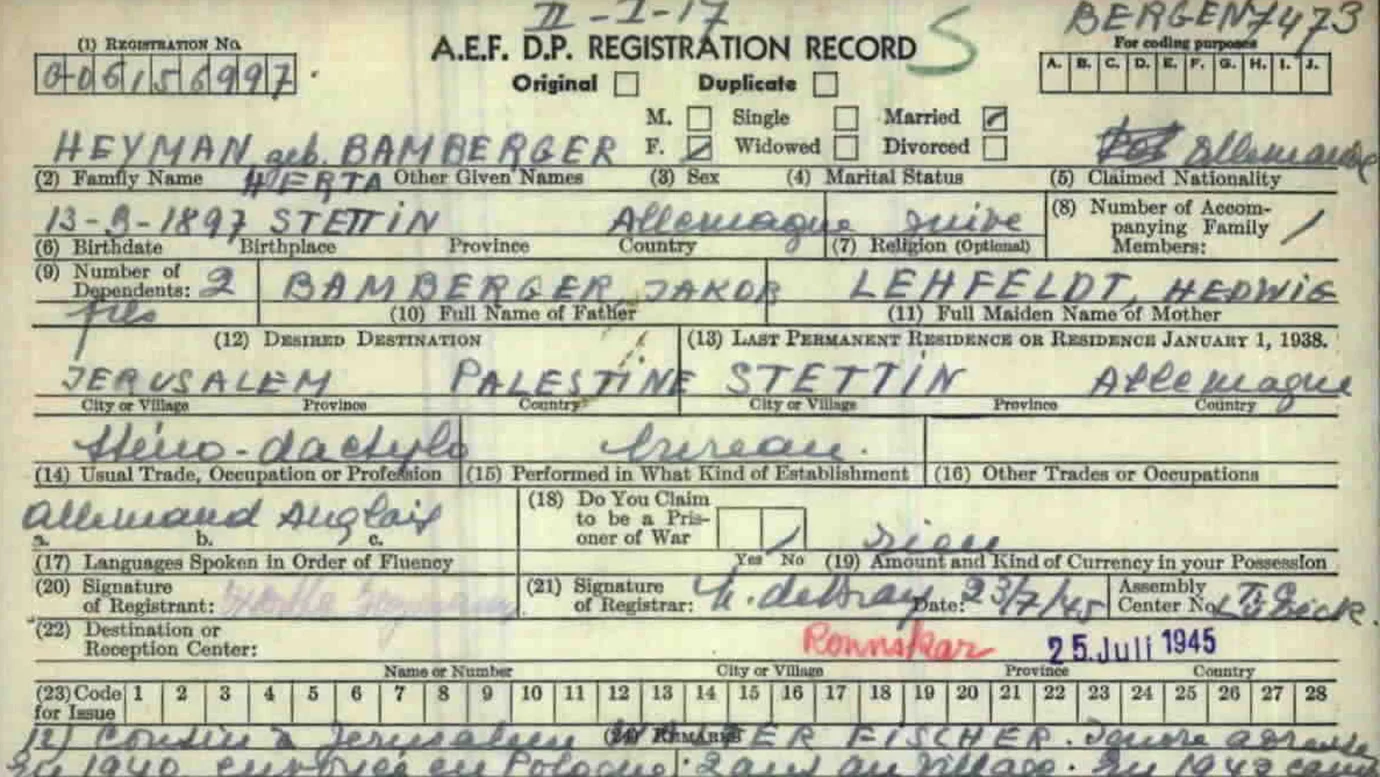

On the April 15, 1945, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British forces. At that time, the camp held more than 60,000 prisoners, most of them Jewish and the majority in a terrible state of starvation and disease. Thousands of dead prisoners were lying unburied in the camp. Hertha and other surviving prisoners were moved out of the camp and received medical care. Meanwhile, the Allied forces tried to register all survivors.

Hertha was one of over 9,000 survivors who were brought to Sweden for treatment by UNRRA transportation. After a period in the transit camp and the Swedish field hospital in Lübeck, she was taken to Sweden on the M/S Rönnskär on July 25, 1945. Rönnskär docked in Ystad the following day and after quarantine and treatment in Ystad and Limhamn, Hertha eventually ended up at Hjälmared's immigration camp in Alingsås.

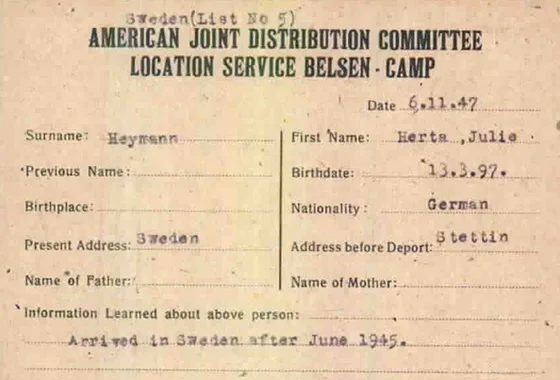

Her son Manfried also survived the Holocaust. This was despite the fact he endured several death marches and his transportation had been attacked by fighter planes in the spring of 1945. During one of the marches, in the town of Stamried in Bavaria, Manfried and other Jews were liberated by American troops. After the war, Manfried managed to get to England, where he immediately tried to find out what had happened to his mother Hertha and brother Eugen. Manfried learnt that Hertha had survived Bergen-Belsen but was ill and in Sweden. He travelled to Sweden in the winters of 1946 and 1947 to be reunited with his mother.

Not long after Manfried's second visit, Hertha died of pulmonary tuberculosis at Söderby Hospital outside Stockholm on the April 4, 1947. She was 50 years old. During her time in Sweden, in addition to being reunited with her one son, Hertha had also been reunited with a cousin who had survived and was now living in Ronneby.

Manfried found his mother's relatives in England and settled there after the war. In 1957, he got married and went on to have two sons. Manfried gave a long and detailed testimony about what happened to him and his family during the Holocaust and registered his relatives in Yad Vashem, giving us an insight into the history of the Heyman family.

Hertha's route

The map shows the places Hertha was forcibly transferred or travelled to, from Stettin where she was born to the Northern Jewish Cemetery. Click on the information symbol to see all the locations, listed in chronological order.

About Hertha Heyman

About Hertha's husband Wilhelm Heyman

About Hertha's son Eugen Heyman

About Hertha's son Manfried Heyman

About Hertha's mother Hedwig Bamberger

Learn more about the fates of other

Here you will find links to the "Förlorade röster" [Lost Voices] collection page as well as links to all the personal texts, listed by surname.