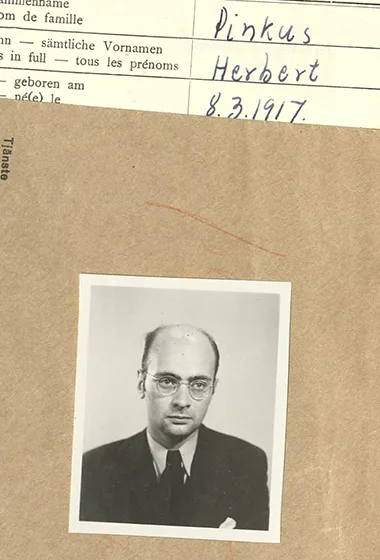

Dresden was a city that flourished during the interwar period, becoming one of the most important cities in Weimar Germany. Herbert's father Max worked as a merchant in Dresden and Herbert had graduated from high school after completing both his primary and secondary school education.

During his last year at school, he must have witnessed how his Germany was changing. When Herbert was about to turn 16, the National Socialists and Hitler came to power in Germany, and in a short time the country became a Nazi dictatorship. Slowly, persecution and discrimination against Jews increased and the situation escalated over the years. Laws were introduced that quickly banned German Jews from serving in most public professions, such as doctors, teachers and lawyers. Jews were also excluded from various organisations and associations, such as sports clubs. Access to higher education was also severely restricted, with only 1.5% of all students allowed to be Jewish.

Herbert still managed to complete his matriculation exam and began studying engineering at the Dresden University of Technology. However, it was not long before the persecution worsened. In September 1935, the Nazis passed the Nuremberg Laws, which legally and socially separated Jews from non-Jews in the country. Jews were no longer allowed to marry non-Jews and many Jews lost their citizenship. Shortly after, in August 1937, Herbert's father Max died. Whether his death was caused by the persecution can neither be proven nor refuted from the remaining documents.

In November 1938, the situation for the Jews deteriorated further, but Herbert managed to finish his studies and obtained his engineering degree. He had his German passport confiscated and cancelled and, along with other German Jews was forced to apply for a new passport. Both Sweden and Switzerland had made it clear to Nazi Germany that they simply wanted to separate Jews from non-Jews, to stop the increasing flow of refugees. The new passports came stamped with the large red letter 'J'.

The November Pogrom, a major act of violence by Nazis against Jews across the German Reich, escalated on the night between November 9–10, 1938, Days earlier, a desperate Jewish youth whose parents had been deported to Poland, had murdered a German diplomat in Paris. This was used as a pretext to carry out the pogrom that had already been planned. It lasted from the November 7–13 and over 1,400 synagogues were burned and destroyed throughout Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland. An additional 7,500 Jewish shops were vandalized and demolished. The streets were littered with piles of broken glass from shop windows, which is said to have prompted the event being referred to 'Kristallnacht'.

Over 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald. Two of these were Herbert and his younger brother Günther, who were both arrested and sent to Buchenwald. They were probably held in Buchenwald for a little over a month but later released. Shortly afterwards, they and their mother Johanna moved to Hamburg. They lived with a woman named Ruth Körbchen at the centrally-located address Lange Reihe 111 in the St. Georg neighbourhood, not far from Hamburg Cathedral. There, Herbert took a job at the Berthold & Wachtel milling machine factory on the outskirts of the city.

With the outbreak of war, persecution increased as the Nazis began the genocide of Europe's Jews in the areas they had conquered. In September 1941, the compulsory wearing of a yellow Star of David to identify Jews was introduced and shortly afterwards Adolf Hitler decided that Germany's Jews would be deported to the east to die in ghettos, concentration camps, extermination camps or mass graves.

On October 25, 1941, Ruth Körbchen, with whom the Pinkus family had lived, was deported to the Łódź Ghetto in Poland. In May 1942, she was deported from the ghetto and most likely taken to the Chełmno extermination camp where she was murdered. Less than two weeks after Ruth's deportation, the Pinkus family's German citizenship was revoked and they were put on trains heading east to the ghetto in Minsk. Johanna was not originally on the list but chose to accompany her sons rather than be separated from them. On the street outside the gate of Lange Reihe 111, there are now four Stolpersteine ("stumbling stones") in memory of Ruth, Herbert, Günther and Johanna.

Herbert, Günther and Johanna were deported to Minsk and placed in a separate ghetto with nearly 24,000 other Jews from Germany and Austria. Many of Minsk's Jews had recently been murdered in massacres on the outskirts of the city to make room for the newly-arrived Jews from the German Reich. The vast majority of Jews who came to Minsk were taken to the camp in Maly Trostenets where they were murdered. Herbert's mother Johanna and brother Günther appear to be two of the more than 40,000 people murdered there.

Herbert's background as an engineer seems to have saved him from the same fate. Instead, he was subjected to slave labour as a repairman for the German Air Force – the Luftwaffe – in Minsk. After three and a half years there, he was transferred to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in February 1945. In the overcrowded and disorganised camp, diseases such as dysentery, diphtheria, typhus and tuberculosis spread and killed thousands. When Herbert arrived at Bergen-Belsen, all his personal documents and possessions were burned by SS men, including his diplomas and certificates.

Liberation and time in Sweden

On the April 15, 1945, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British forces. At that time, the camp held over 60,000 prisoners, most of them Jews and the majority in a terrible state of starvation and disease. Thousands of dead prisoners were lying unburied in the camp. Herbert and other surviving prisoners were moved out of the camp and received medical care. Meanwhile, the Allied forces tried to register all survivors.

What happened to Herbert in Bergen-Belsen in the final months before liberation is a little vague, but he seems to have fallen ill with some kind of disease. He was one of over 9,000 survivors brought to Sweden by UNRRA transportation for treatment. After a period in the transit camp and Swedish field hospital in Lübeck, he was taken to Sweden on HMS Prince Carl on the July 11, 1945. The ship docked in Kalmar after a four-day voyage and Herbert was admitted to the emergency hospital set up at Vasaskolan, a local school. After a period at the emergency hospital and the former infirmary in Kalmar, he was sent to the Berga immigration camp in Nykvarn, before being given the opportunity to move to Stockholm. Herbert had received a certificate from the doctors in the camp that he was in good health and able to work. In Stockholm, Herbert started working as a mechanical engineer for Sandblom & Stahne on the west side of Kungsholmen in Stockholm.

It was probably in Stockholm that Herbert met his wife Eva, born Mandel, who also seems to have been a Holocaust survivor. Eva came from Budapest. It is likely that she arrived with the UNRRA transportation to Sweden at the same time as Herbert. They lived together in Stockholm for a little more than a year, but Herbert was hospitalised at Serafimer Hospital for several months in both 1946 and 1947. Documents in the Swedish archives testify to the strong desire he had to build a new life in Sweden. He started a family and tried to find work as an engineer but fell ill repeatedly. Herbert died aged 30 on the July 25, 1947, barely two years after arriving in Sweden, due to injuries sustained during the war. He left behind his young widow Eva.

Herbert's route

The map shows the places Herbert was forcibly transferred or travelled to, from Dresden where he was born to the Northern Jewish Cemetery. Click on the information symbol to see all the locations, listed in chronological order.

About Herbert Pinkus

About Herberts mother Johanna Pinkus

About Herbert's brother Günther Pinkus

About Herbert's father Max Pinkus

Learn more about the fates of other

Here you will find links to the "Förlorade röster" [Lost Voices] collection page as well as links to all the personal texts, listed by surname.