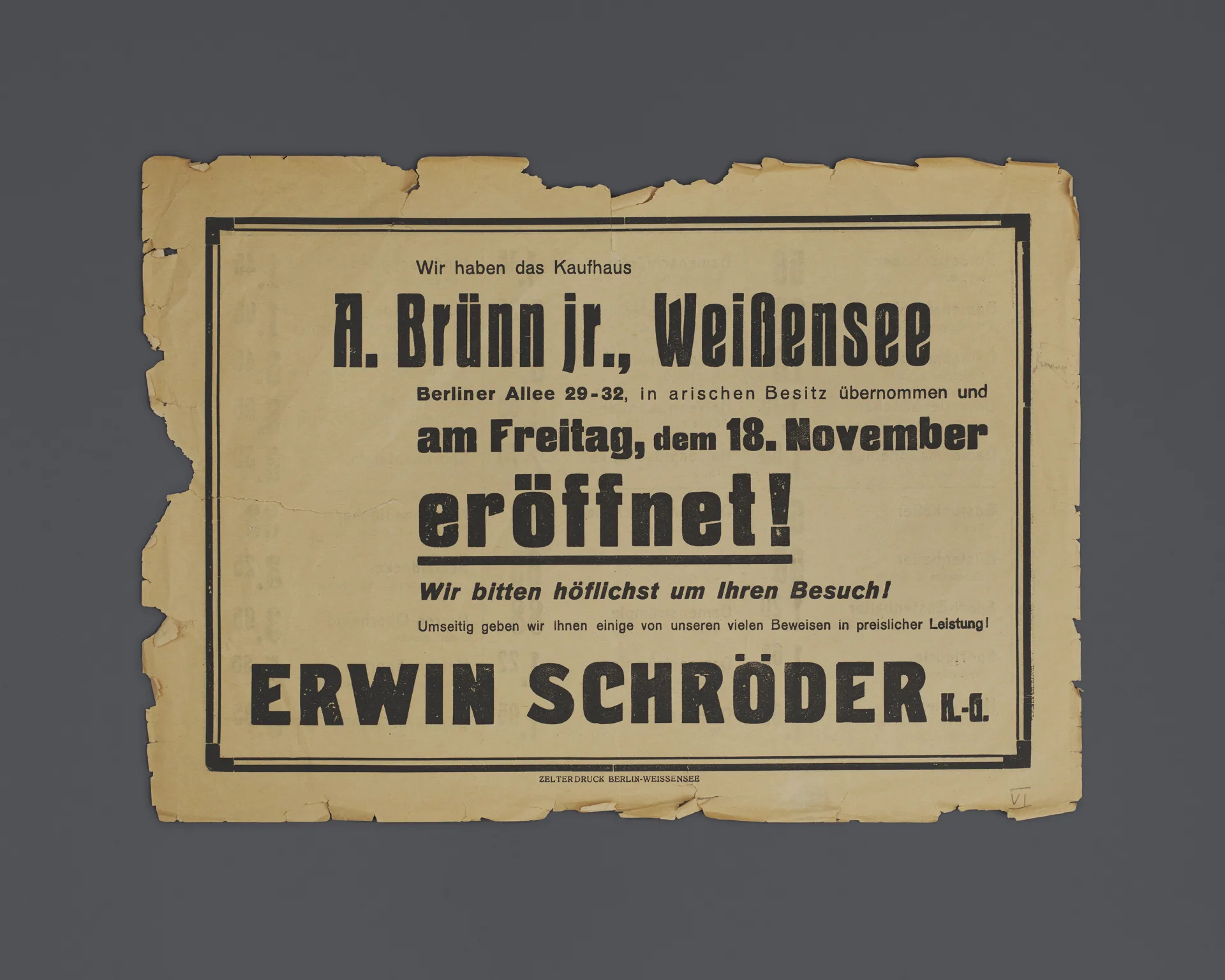

Immidiately after Noveberpogrom, the night of 9–10 November 1938, Walter Brünn was temporarily imprisoned in the Sachsenhausen labour camp. The German authorities seized the family business and handed it over to a so called 'Aryan' proprietor.

The antisemitic policies pursued by Nazi Germany during the 1930s included systematically excluding the Jews from the labour market by seizing their businesses and prohibiting them from practicing various professions. The Nazis were determined to make it as difficult as possible to live in Germany. Increasing numbers of Jews attempted to emigrate, but were denied entry visas to other European countries and the United States. Although the Swedish border was never closed, it was more difficult for Jewish refugees to obtain a residence permit than for non-Jews.

My father is elderly and fragile, he currently weighs a mere 49 kilograms. It is in the nature of things that I have a heartfelt desire to see him here close to me during the final years – or perhaps months – he has of life.’

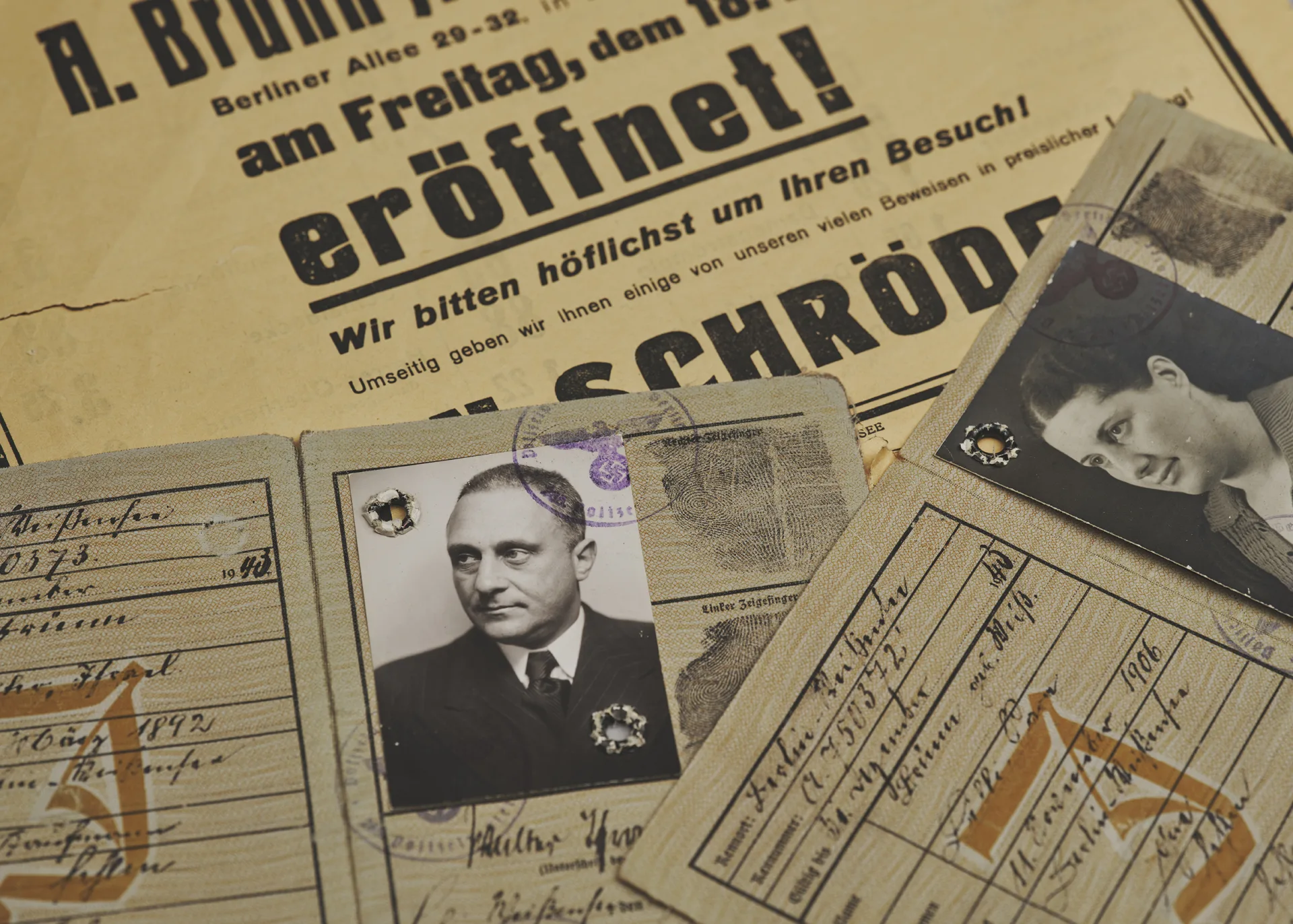

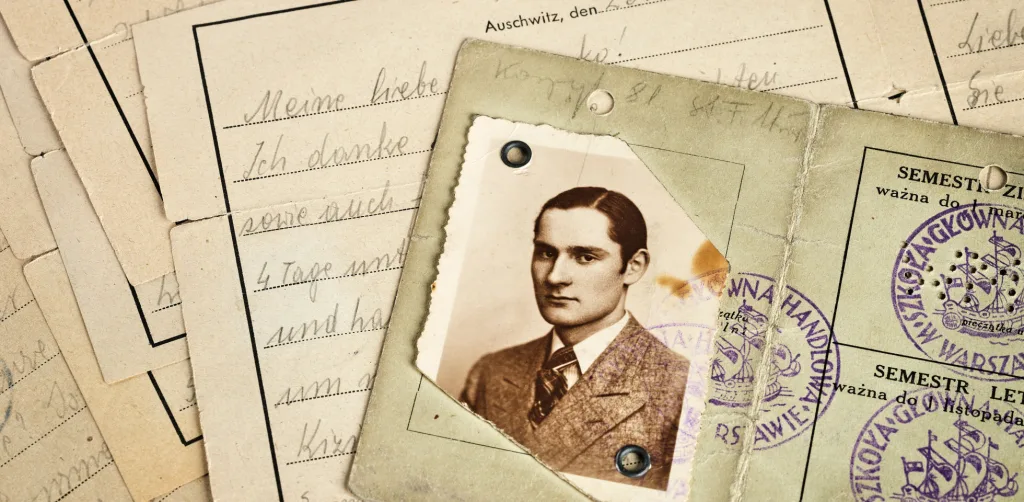

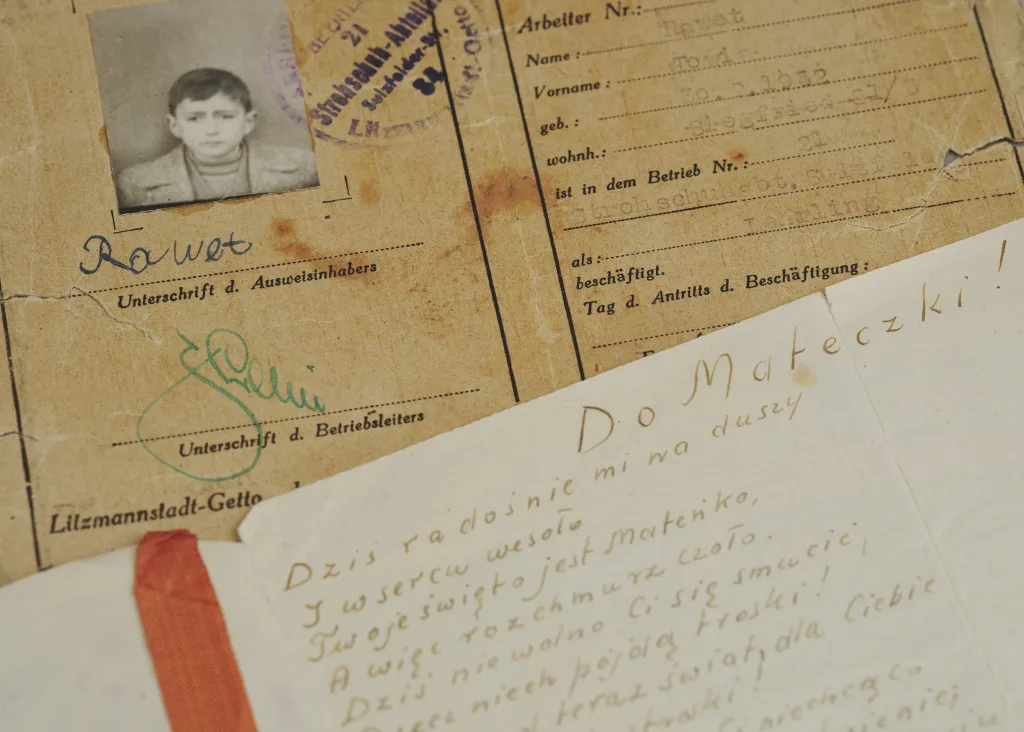

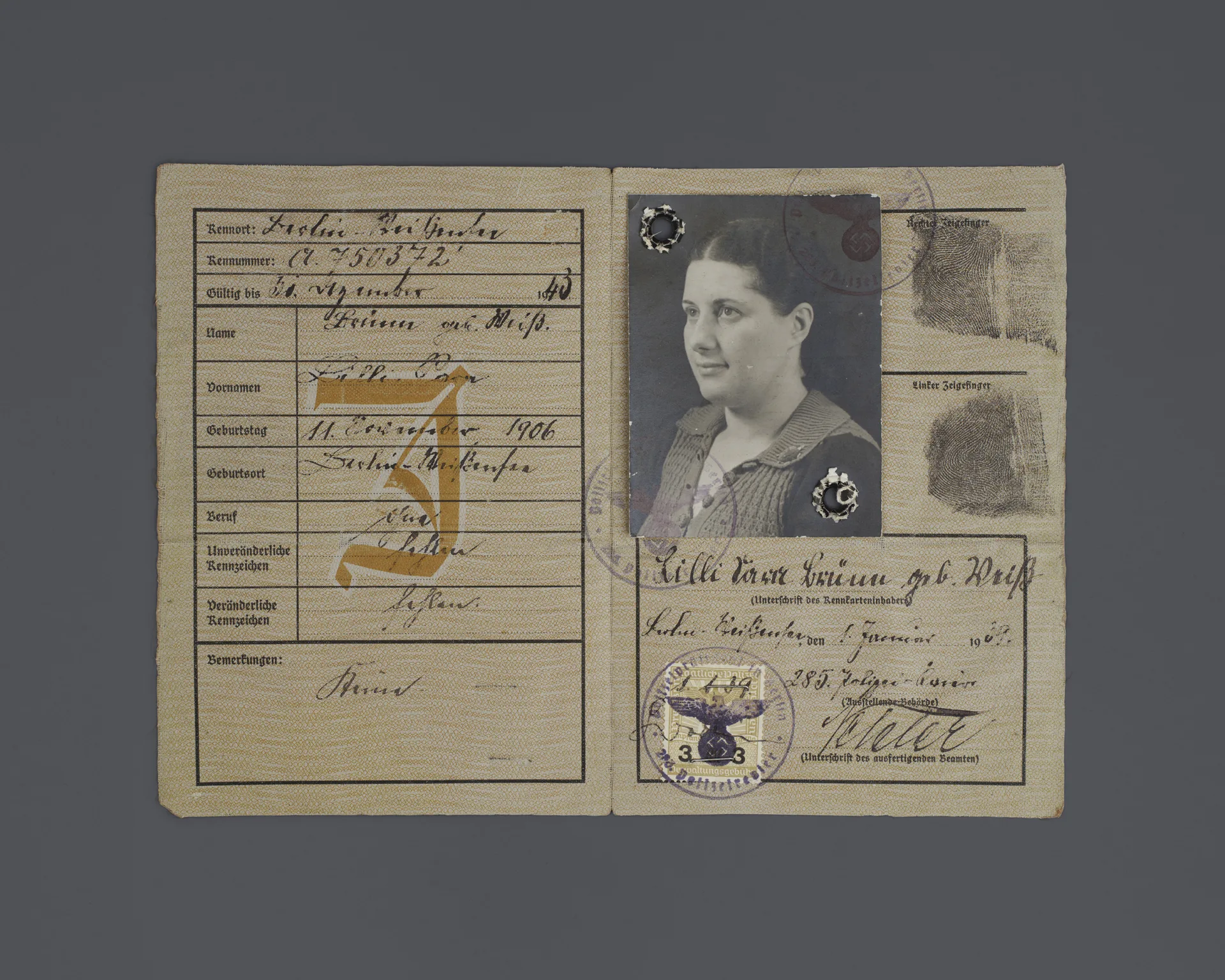

Both Lilli’s and Walter’s identity cards were stamped with a large letter J. As more Jews attempted to flee in the wake of the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, Sweden and Switzerland requested that the Germans distinguish Jews from non-Jews or they would impose visa requirements. To this end, the Germans began to stamp the passports, and identity cards, of all Jewish citizens with the letter J, in order to separate Jews from non-Jews.

Marianne Hede about Lilli and Walter's identity cards

Lilli and Walter were eventually granted Swedish residence permits and they settled in Södermalm, Stockholm. In the years 1938 and 1939, some 2,000 Jewish refugees were granted residence permits in Sweden. Lilli and Walter appealed to the Swedish authorities to allow their parents to come to Sweden. In a letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs dated 11 September 1941, Walter writes:

‘My father is 80 years old, alone and widowed; I am his only child. (…) For several weeks now, I have been receiving heartrending letters, especially because conditions in Germany are presently absolutely unbearable for Jews. If I may point out here, the situation has deteriorated over the past few weeks since the introduction of ‘marking’ Jews (with yellow stars on their clothing). My father is elderly and fragile, he currently weighs a mere 49 kilograms. It is in the nature of things that I have a heartfelt desire to see him here close to me during the final years – or perhaps months – he has of life.’

Neither Walter’s father nor Lilli’s parents were granted residence permits. Walter’s father died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Lilli’s parents were deported to Lublin in 1942. They did not survive the Holocaust.

Header photo: Detail of Lilli's and Walter's passports and other documents. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish Holocaust Museum/SHM.

Source:

- The museum’s collection. Lilli’s and Walter’s identity card, as well as letters and other documents belonging to the couple, have been saved by their former neighbours in Södermalm, Stockholm. The neighbours subsequently donated the material to the Swedish Holocaust Museum.

- Geverts, Karin Kvist. A Foreign Element within the Nation: Swedish Refugee Policy and the Jewish Refugees 1938–1944. Uppsala 2008.