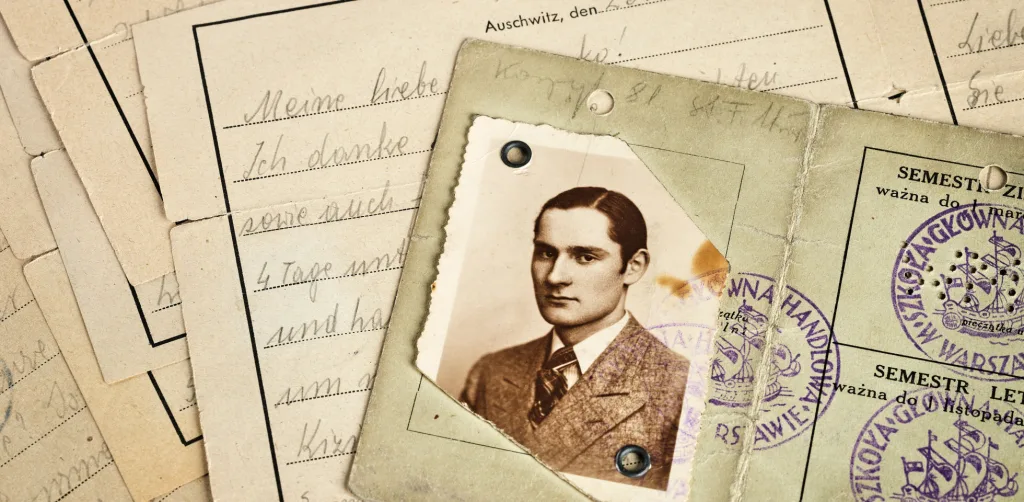

Czesław Aredzki was from a non-Jewish, Polish middle-class family. In 1939 he was 24 years old and had been at cadet college for a year. He studied at the Warsaw School of Economics and was engaged to a girl called Krystyna.

When Germany attacked Poland, Czesław was sent to the front as a non-commissioned officer in the Polish army. The German army drove them back eastwards and Czesław ended up in a Soviet prisoner of war camp.

He tore off his badges of rank and was therefore treated as a private instead of an officer. Czesław was released and returned on foot to Poland and his fiancée. They married in Krystyna's home town of Kiońske in February 1941 and Czesław got work in the office of a farming cooperative. Did they perhaps dare to hope that the war would soon be over, so that life could return to normal? Instead, Czesław was arrested by the Gestapo, Nazi Germany’s secret police, in August 1943 and was sent to the camp at Auschwitz.

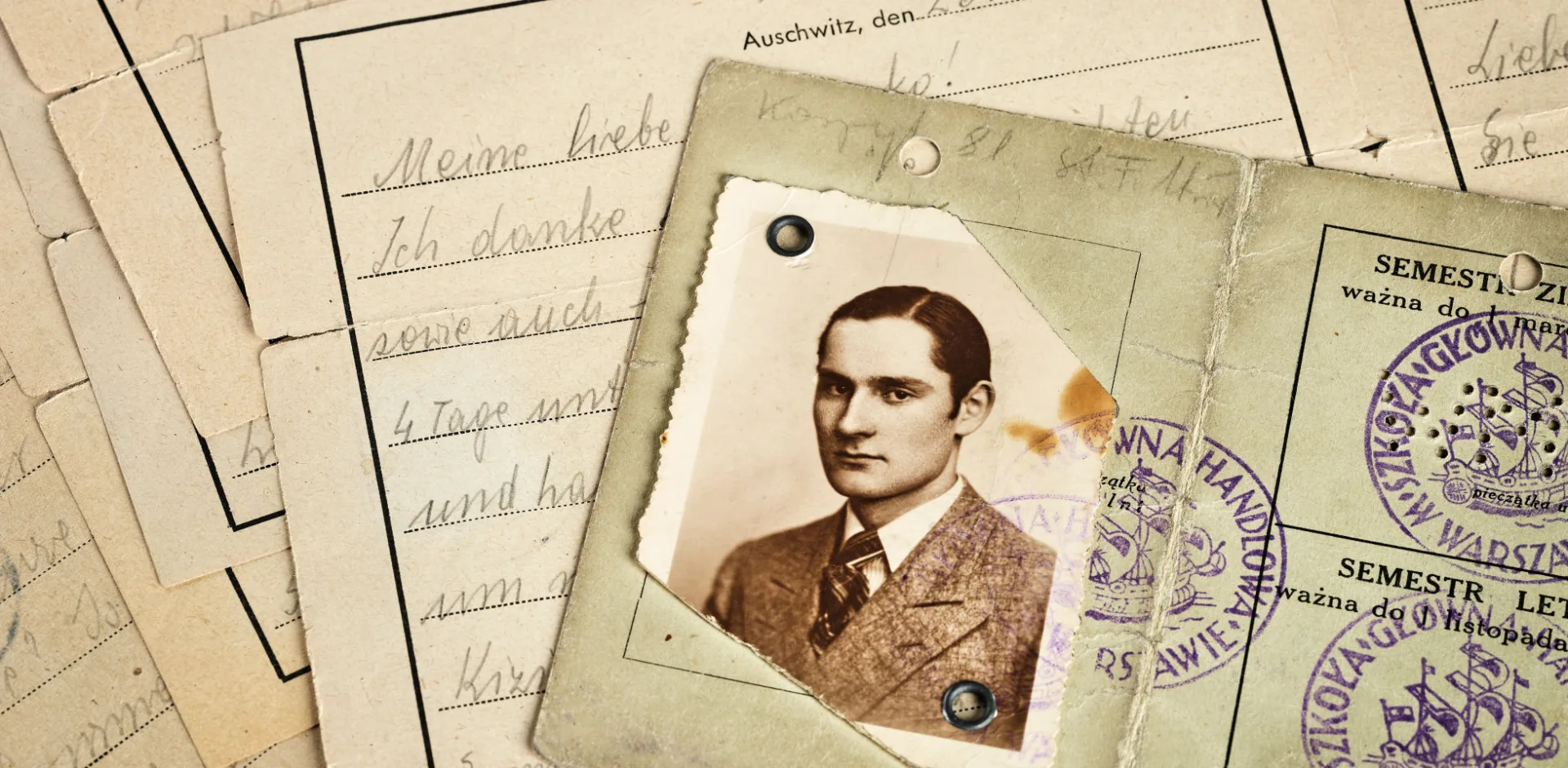

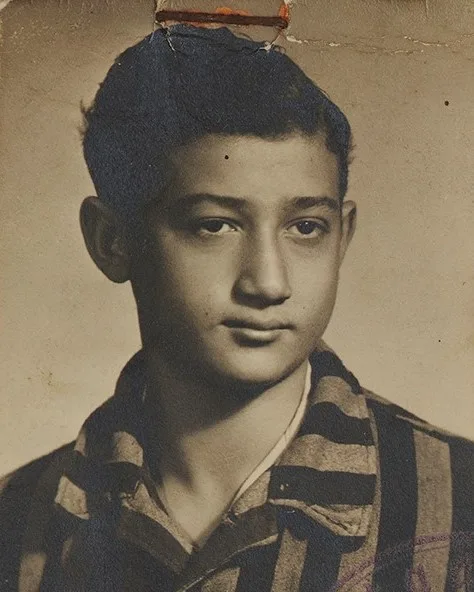

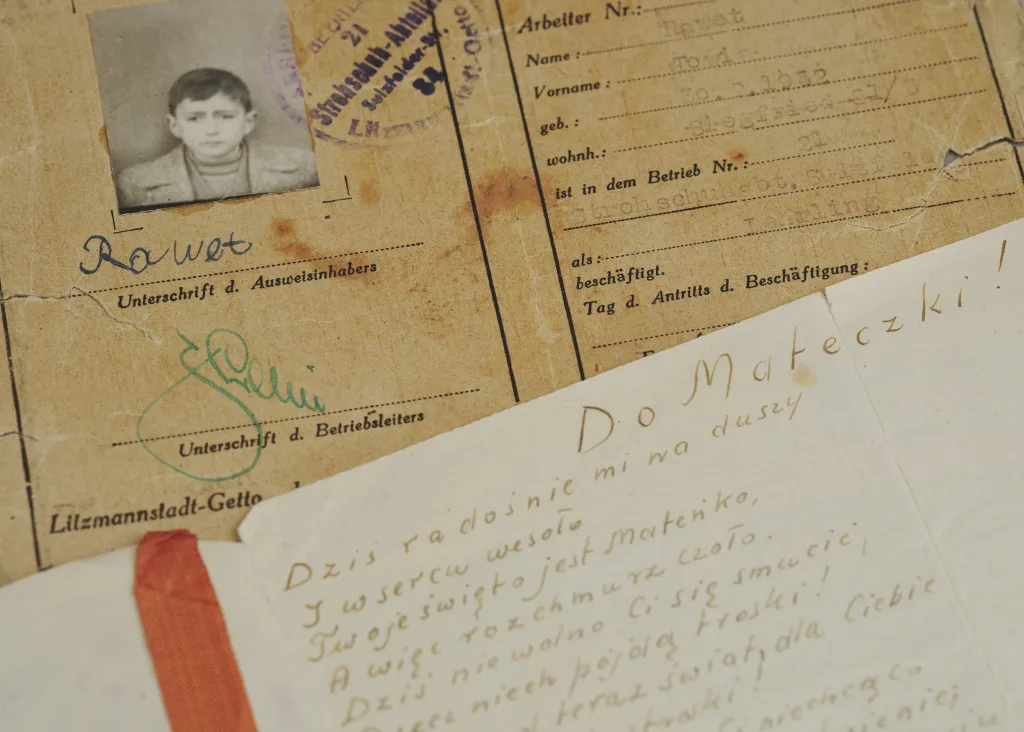

Czesław arrived at Auschwitz on 3 August 1943 and was registered as prisoner number 138009. Because he had been imprisoned as a political prisoner, Czesław was allowed to write letters to his family and receive letters and food parcels.

While he was at Auschwitz, Czesław became very ill with typhoid and was moved to the hospital barracks. There, he finally became so weak that he lost consciousness. He was carried out together with those that had died, but he woke up again. When he tried to get up from the heap of bodies, he was noticed by a nurse and a Jewish doctor. They took him back to the hospital barracks. Czesław wrote his last letter from Auschwitz on 8 October 1944. As the Soviet army approached, he was moved between several concentration camps in Germany before being released.

One of Czesław's letters

“Auschwitz on 12 September 1943.

My dear Kristina!

Please send parcels up to 10 kg with bread, onions, lard, sugar, 15 cigarettes or 50 g tobacco, cigarette paper, pipe, 1 old shirt, underpants, winter socks. My parents will send you 5 stamps of 12 Rf each, which you will send to me. I am healthy and feel well. You can only write 2 times per month. The letters must be in German and legible. Parcels can be sent twice a week. I prefer tobacco to cigarettes. I kiss you heartily and so the whole family.

Your Czeslaw"

Czesław Aredzki

After the war, Czesław was reunited with his wife Krystyna in the city of Łódź. Their son Jerzy was born in 1948. Kristina never thought that Czesław was really himself again after the war and his time in the camps. They divorced in 1954 and Czesław moved to Zakopane. There, he worked as a nature guide and ski teacher in the Tatra Mountains, on the border between Poland and Slovakia. His son Jerzy still lived with Krystyna but visited Czesław in the holidays. Sometimes Czesław guided bus tours to the museum that had previously been the camp at Auschwitz. The museum opened in 1947.

Towards the end of the 1960s, Czesław decided to leave Poland. His son Jerzy, who was in his twenties, decided to go with him. They took the train to Stockholm and got residence permits in Sweden.

Czesław got a job in the central kitchens at Långbro Hospital, where he worked for the rest of his life. He saved up to buy a car so that he could travel around Europe and camp after he retired. But three months before his retirement, Czesław became ill with cancer and he died in Stockholm in 1980 at the age of 65.

Czesław's story

Jerzy Aredzki has shared his father's story with the Swedish Holocaust Museum and has loaned letters, photographs and objects.

Sources

- Museum collections.

- Jerzy Aredzki has shared his father's story with the Swedish Holocaust Museum and has loaned letters, photographs and objects.