She grew up with her parents, David and Anna Abrahamer, and her younger siblings Jakub and Irena. They were among the nearly 70,000 Jews living in the old town of Krakow. The family owned a bakery, where their father David worked as a master baker, and both Sabina and Jakub appear to have helped in the bakery. The Krautwirt family lived in the heart of the city, near the large Rakowicki cemetery, just north of Krakow's historical centre.

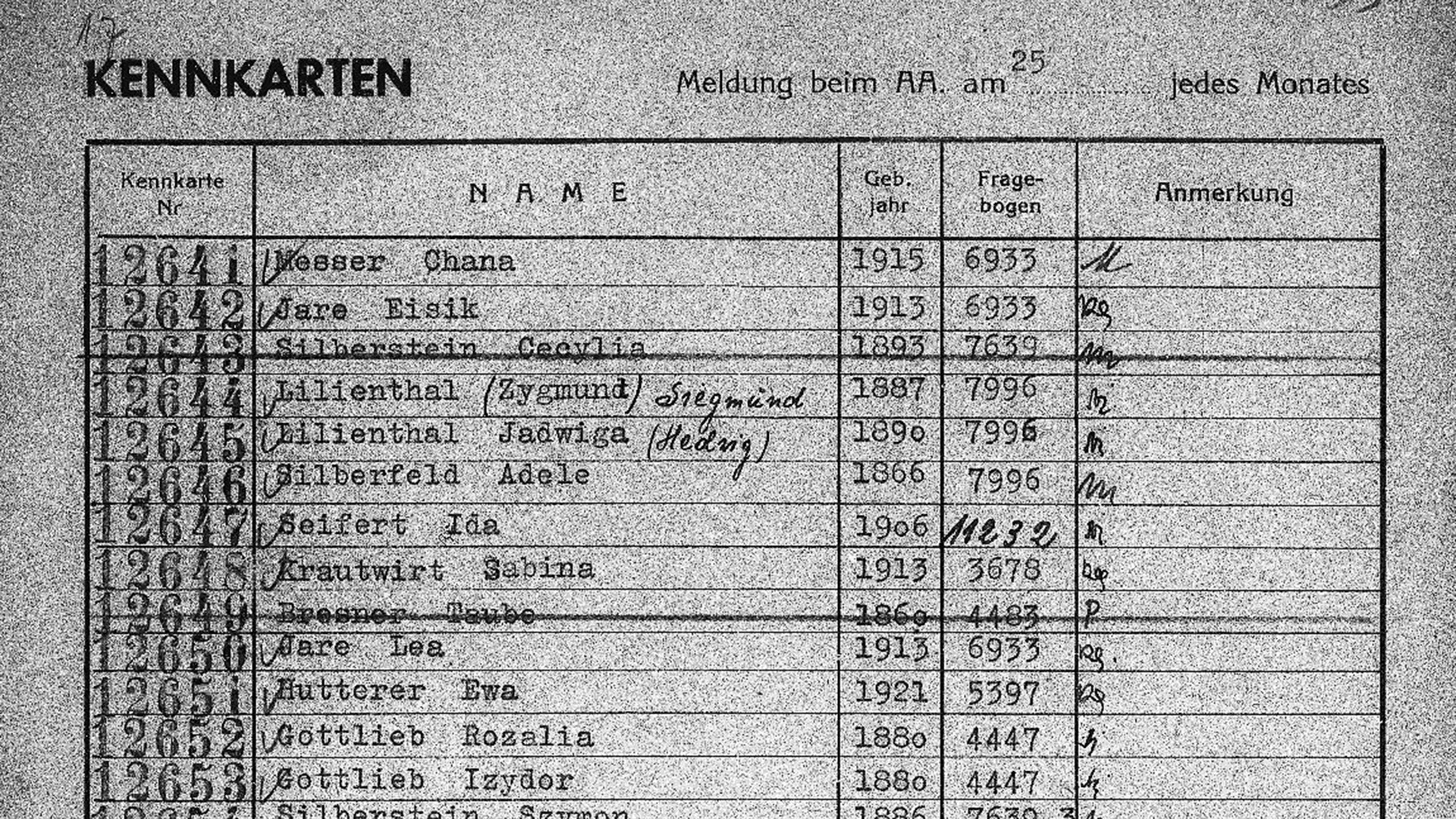

Sabina was 25 years old when German troops marched into Krakow on September 6, 1939, barely a week after the German forces invaded Poland. They wanted to establish Krakow as the seat of the German occupation and rid the city of its Jewish population. The city's Jews began to be persecuted and were discriminated against. They were forced to wear white armbands with blue Stars of David and many were subjected to forced labour. All Jews in the city were registered and had to declare their possessions as well. Synagogues were closed again and Jews were forbidden to enter certain places and use some modes of public transport.

In the spring of 1940, just over six months after the German invasion, the Germans began displacing large numbers of Krakow's Jews to the east, in the countryside and area close to the Polish city of Lublin. Initially, Jews were offered the chance to keep their property if they moved voluntarily, but it wasn't long before they were forcibly relocated. In total, over 50,000 Jews were expelled from Krakow. Most of them were later murdered during the Holocaust, many in the Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka extermination camps.

Only 15,000 Jews remained in Krakow, those which the Germans considered 'economically useful', including Sabina and her family. Just a few months later, in March 1941, the remaining Jews were forced into the ghetto the Germans had established in the city. The chosen area was the run-down Podgórze neighbourhood, across the Vistula River from Krakow's Old Town. The traditional Jewish quarter of Kazimierz, where Jews had lived since the 14th century, would instead become part of the new aryanized city the Germans wanted to establish.

When the Krakow Ghetto was established, Sabina had recently married a man named Mojesz Krautwirt. It is not entirely clear whether Mojesz and his parents were already living in the ghetto area or whether they had been forced to move there. Sabina moved into the ghetto with her family and it is certain that they were forced to move there. Each person was only allowed to take 25 kg of belongings with them, while the remaining assets the Jews left behind were confiscated by the Germans. There were now 15,000 people living in the small Podgórze neighbourhood, where previously no more than 3,500 people had lived. From time to time, more Jews arrived in the ghetto after being deported there.

Initially, the ghetto was not closed and some Jews were allowed to work outside but in October 1941 the ghetto was sealed off. Jews who left the ghetto without authorisation were punished by death. Previously, everyday life in the ghetto had continued, largely because many Jews were allowed to work outside the ghetto and able to buy food and supplies for their families. But without access to sufficient food and enormous overcrowding, the misery and suffering in the ghetto became severe. Many Jews were subjected to slave labour in the Płaszów concentration and labour camp, which the Germans established south of the ghetto.

After moving to the ghetto, traces of Sabina and her family begin to disappear. In the spring and summer of 1942, the Germans officially began moving people from the ghetto down to the Płaszów camp, while in reality thousands were deported to the Bełżec extermination camp where they were immediately murdered. During the summer and autumn of that year, nearly 15,000 Jews from the Krakow Ghetto were murdered. It seems that most members of the Abrahamer and Krautwirt families were among those murdered. The ghetto’s lists of “employable people” include Sabina's brother and husband, but neither her or Mojesz’s parents nor her sister Irene. After the war, Sabina stated that her parents were dead. Her brother Jakub appears to have moved in with Sabina and her husband Mojesz, but shortly thereafter the traces of Mojesz cease. At the end of the war, Sabina states that she is a widow.

Sabina and her younger brother Jakub remained alone in the harsh ghetto until it was evacuated in March 1943. Almost 2,000 Jews were shot in the process while the remaining 2,000, including the Abrahamer siblings, were transferred to the Płaszów concentration camp. There the Jews were subjected to hard slave labour, particularly in factories. After one and a half years together in the camp, Jakub was transferred to the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria on October 16, 1944. He and other prisoners were forced to work in quarries, where conditions were worse than many other labour camps and duties were extremely physically demanding. Prisoners in the camp suffered from a lack of clean water, poor hygiene and were poorly dressed for the cold weather. On the March 3, 1945, Jakub was murdered in the Flossenbürg concentration camp and cremated there. He was 27 years old.

Sabina seems to have survived in Płaszów until January 1945, despite daily shootings, deportations and horrendous conditions. Most prisoners in the camp had already been murdered or, like Jakub, deported by this time, but Sabina appears to have been one of over 600 prisoners remaining in the camp. The Soviet forces were now closing in, and Sabina and the others were forced to leave and walk to Auschwitz on foot in the bitter cold, a distance of almost 50 kilometers.

From Auschwitz, Sabina seems to have been transported further west, ending up in Bergen-Belsen, where other tens of thousands of Jews were also moved as the Allied forces came closer. Like Sabina, many of the prisoners had been forced on death marches in the harsh January and February weather before arriving in Bergen-Belsen if they survived. In the overcrowded and disorganised camp, diseases such as dysentery, diphtheria, typhus and tuberculosis spread. The sicknesses killed thousands and Sabina became severely ill with fever, diarrhea and typhus.

Liberation and time in Sweden

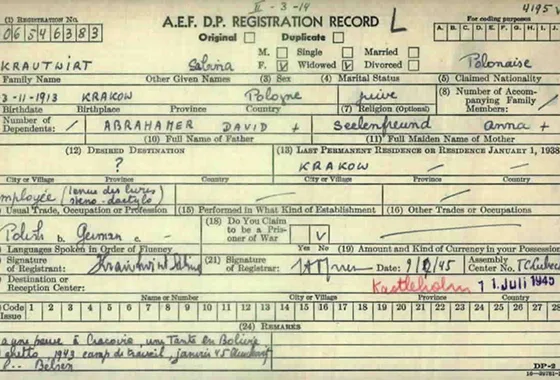

On the April 15, 1945, Bergen-Belsen was liberated by British forces. At that time, there were over 60,000 prisoners in the camp, mostly Jews and the majority in a terrible state of starvation and disease. Thousands of dead prisoners were lying unburied in the camp. Sabina and other survivors were moved out of the camp and received medical care. Meanwhile, Allied forces tried to register all survivors. On her registration card, she states that her parents and husband are dead and her closest relative is an aunt or uncle in Bolivia.

Sabina was one of over 9,000 survivors brought to Sweden for treatment by UNRRA transportation. After a period in the transit camp and the Swedish field hospital in Lübeck, a seriously ill Sabina was taken to Sweden on the S/S Kastelholm on July 11, 1945. The Kastelholm docked in Stockholm after a four-day voyage. Sabina was in such poor health that she was immediately sent to the Epidemic Hospital in Roslagstull, just a few kilometres from Frihamnen where the boat had arrived. Doctors at the hospital tried desperately to save her life, but on August 5, at 2:25pm she died of her severe injuries at the age of 32.

It seems that Sabina was the only member of her family who was alive during the liberation. In her and her family's case, there is no survivor who registered any family members. Traces of the existence of Sabina and the Abrahamer and Krautwirt families are the few documents that exist in the archives.

Sabina's route

The map shows the places Sabina was forcibly transferred or travelled to, from Krakow where she was born to the Northern Jewish Cemetery. Click on the information symbol to see all the locations, listed in chronological order.

About Sabina Krautwirt

About Sabina's husband Mojesz Krautwirt

About Sabina's father David Abrahamer

About Sabina's mother Anna Abrahamer

About Sabina's brother Jakub Abrahamer

About Sabina's sister Irena Abrahamer

Learn more about the fates of other

Here you will find links to the "Förlorade röster" [Lost Voices] collection page as well as links to all the personal texts, listed by surname.