Hanna spent the first eight years of her life in western Poland with her Roma family. When Germany attacked Poland in September 1939, Hanna’s mother had only recently died. Her father set off with the family to move further away from the front. The journey would have been too much for Hanna and her little sister, so they remained behind in the care of an aunt. Their father promised to return for them but he and the rest of the family were confronted by German soldiers outside the aunt’s house. Hanna and Anita watched through the window as the entire family was gunned down. The soldiers returned to the house and shot the aunt and uncle.

Hanna and Anita were spared on this occasion but were later transported to the concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. Hanna was 10 years old, Anita three years younger, and she remembered clutching her sister’s hand tightly throughout the ordeal, afraid they would be separated. After only a few weeks in the camp, Anita was selected among the countless number to be murdered in the gas chambers.

After Anita’s death I began to understand that the only way to survive was to cut myself off from my emotions. One could have no compassion for the other prisoners. There was one thing to be done and that was to try to survive.

Hanna managed to survive the thinning out of inmates for several years. She exaggerated her age, making herself a candidate for forced labour, and was moved from Auschwitz-Birkenau to various labour camps. She endured heavy labour and various types of assault. For a while she was held in the Majdanek concentration and extermination camp on the outskirts of Lublin. According to Hanna herself, this was the worst of the camps. In Majdanek, everyone was resigned to their imminent death. One day, it was Hanna’s turn. She was tied to a Jewish girl of her own age and placed in the left-hand column, those who were to die.

As Hanna remembered it, they spent what seemed like an entire day tied to one another, waiting in the queue for death. Then a new order was issued; all able-bodied prisoners were to be shipped to a factory in Hamburg, Hanna included.

The final labour camp in which Hanna was held was Ravensbrück. One day, white ambulances arrived at the camp and the prisoners were informed that the war was over. This was the Swedish Red Cross operation the White Buses. Hanna and her cousin Sofia arrived in Sweden on the White Buses in spring 1945, survivors of the genocide of the Roma. They were two of the few Roma whom entered Sweden at the end of the war, as the country maintained a ban on non-Swedish Roma entering the country until 1954.

The icon. Berith Kalander tells.

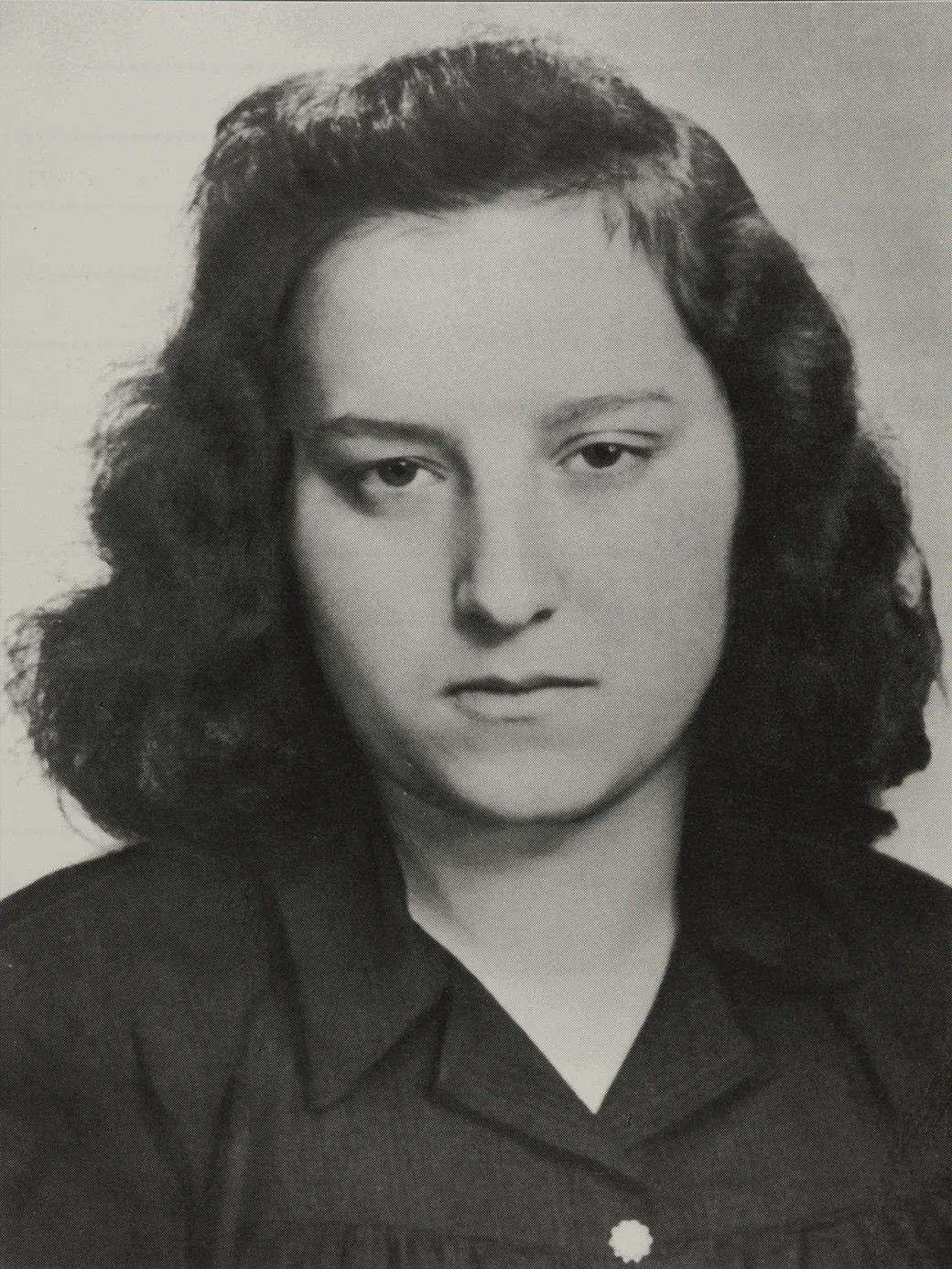

Header photo: Photo of portrait of Hanna Dimitri (Brezinska), with the icon in the background. Photo: Swedish Holocaust Museum/SHM.

Sources:

- Hanna’s testimony has been passed on to the museum by survivors.

- Icon lent to the Swedish Holocaust Museum.

- Kalander, Berith. 1996. Min mor fånge Z-4517. [My Mother Prisoner Z-4517]. Publication series No. 2. Gällivare: Gällivare Municipal Public Library.

- Kalander, Berith. 2015. Sörj inte lidandet välkomna livet [Grieve Not Suffering, Welcome Life]. Öjebyn: Berith Kalander cop.

- Lundgren, Gunilla. 2005. Sofia Z-4515. Stockholm: Tranan.