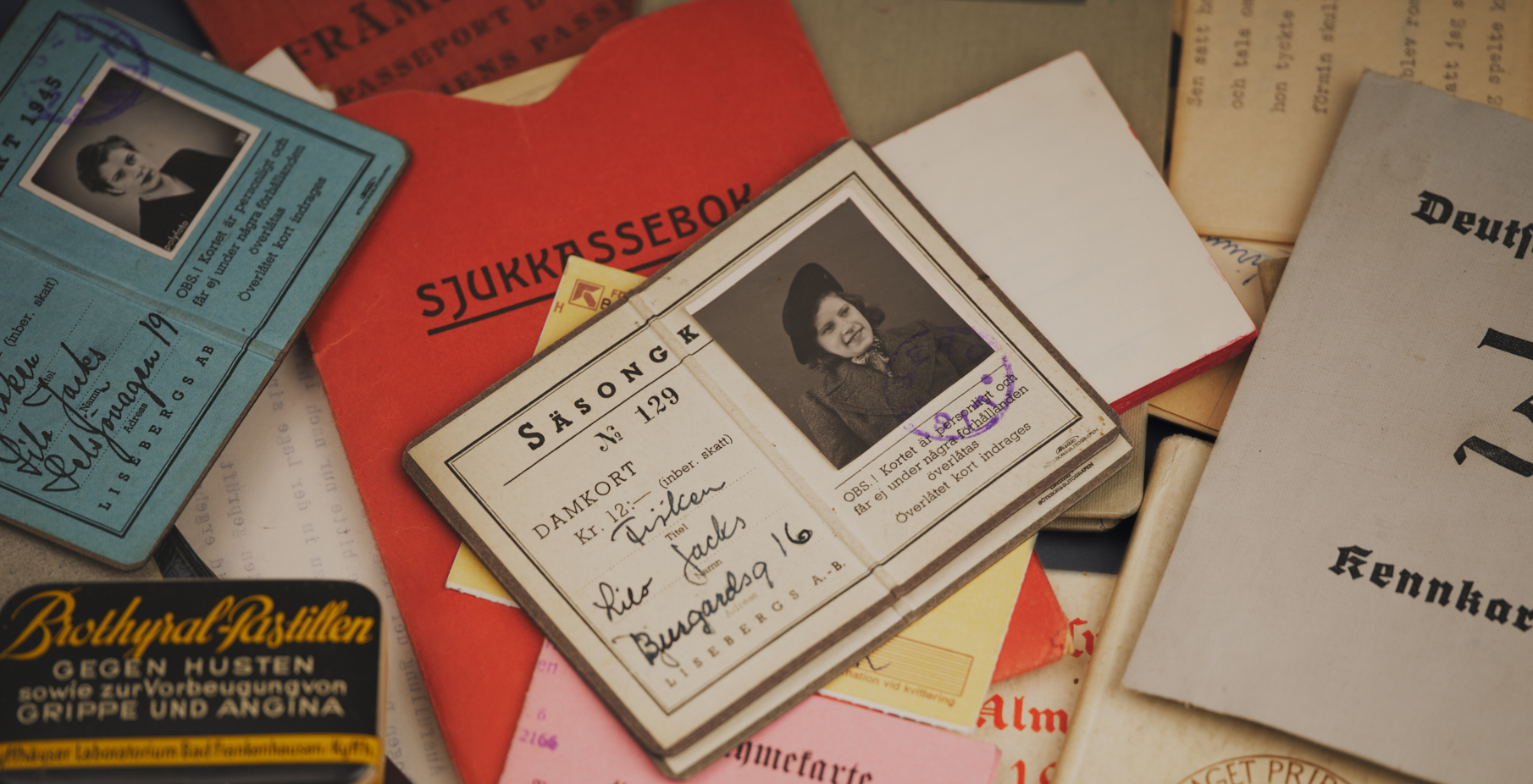

Lieselotte, or Lilo as she was known, saved a number of mementos of the war years, including the small suitcase she carried with her on the train and letters from her parents and grandmother Rosalie. Born in 1923, Lieselotte grew up in Berlin with her parents Gertrud and Alfred. From 1933, when the National Socialists came to power, hundreds of laws, decrees and regulations were passed to make life harder for the Jews in Germany. On Novemberpogrom, the pogroms of 9–10 November 1938, synagogues in Nazi Germany and Austria were burned down, Jewish businesses vandalised and Jews assaulted and murdered; some 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and detained in concentration camps.

Do you have news from your parents?

This violence was met with consternation around the world and initiatives were taken to rescue Jewish children from Nazi Germany on the Kindertransport (children’s transport). Lieselotte was one of the children onboard the Kindertransport organised by the Mosaic Congregation’s Relief Committee. The United Kingdom welcomed some 10,000 Jewish children. For its part, Sweden accepted around 500.

The last time Lieselotte saw her parents was when they waved her off on the train from Berlin in 1939.

The suitcase. Greger Brolin tells.

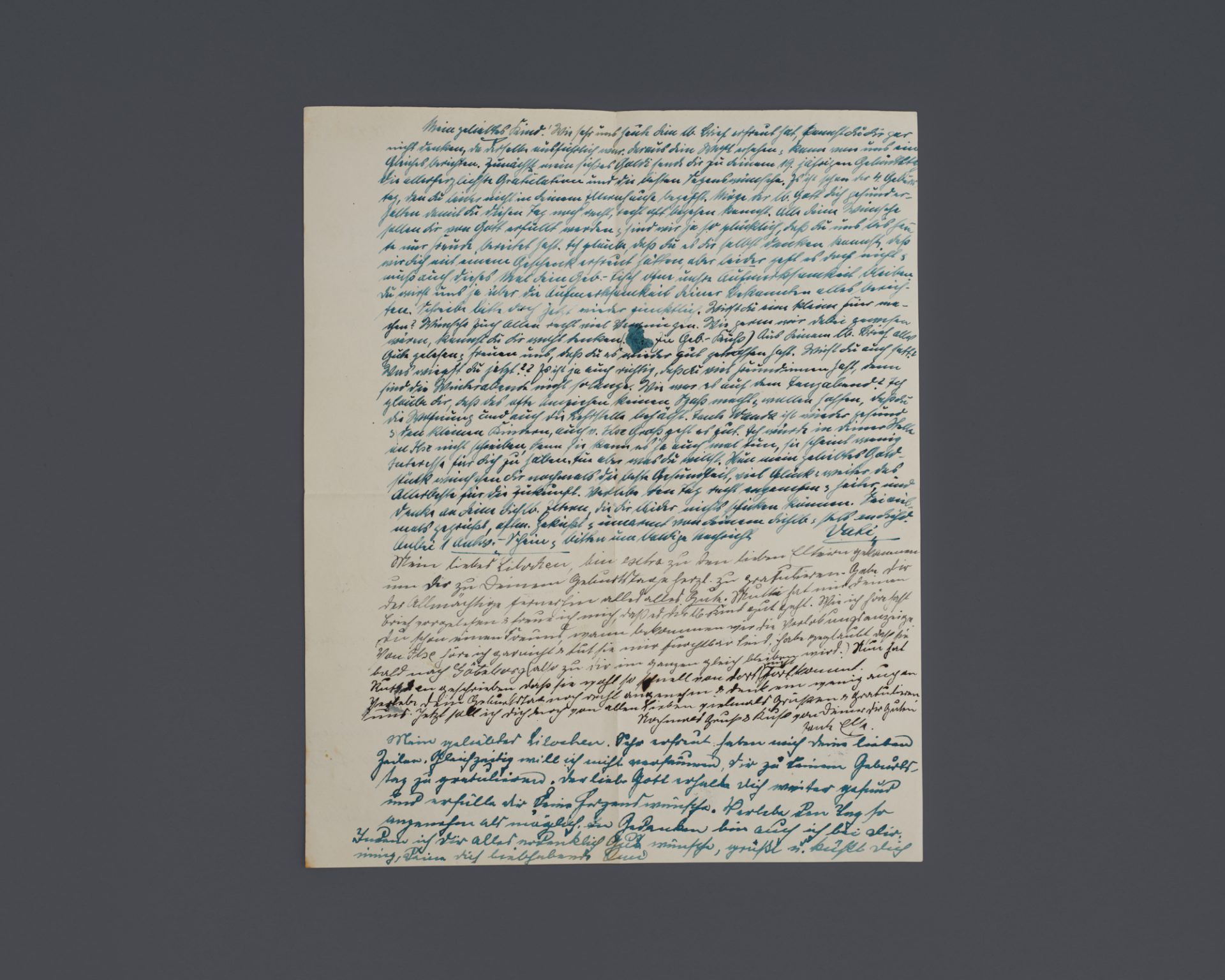

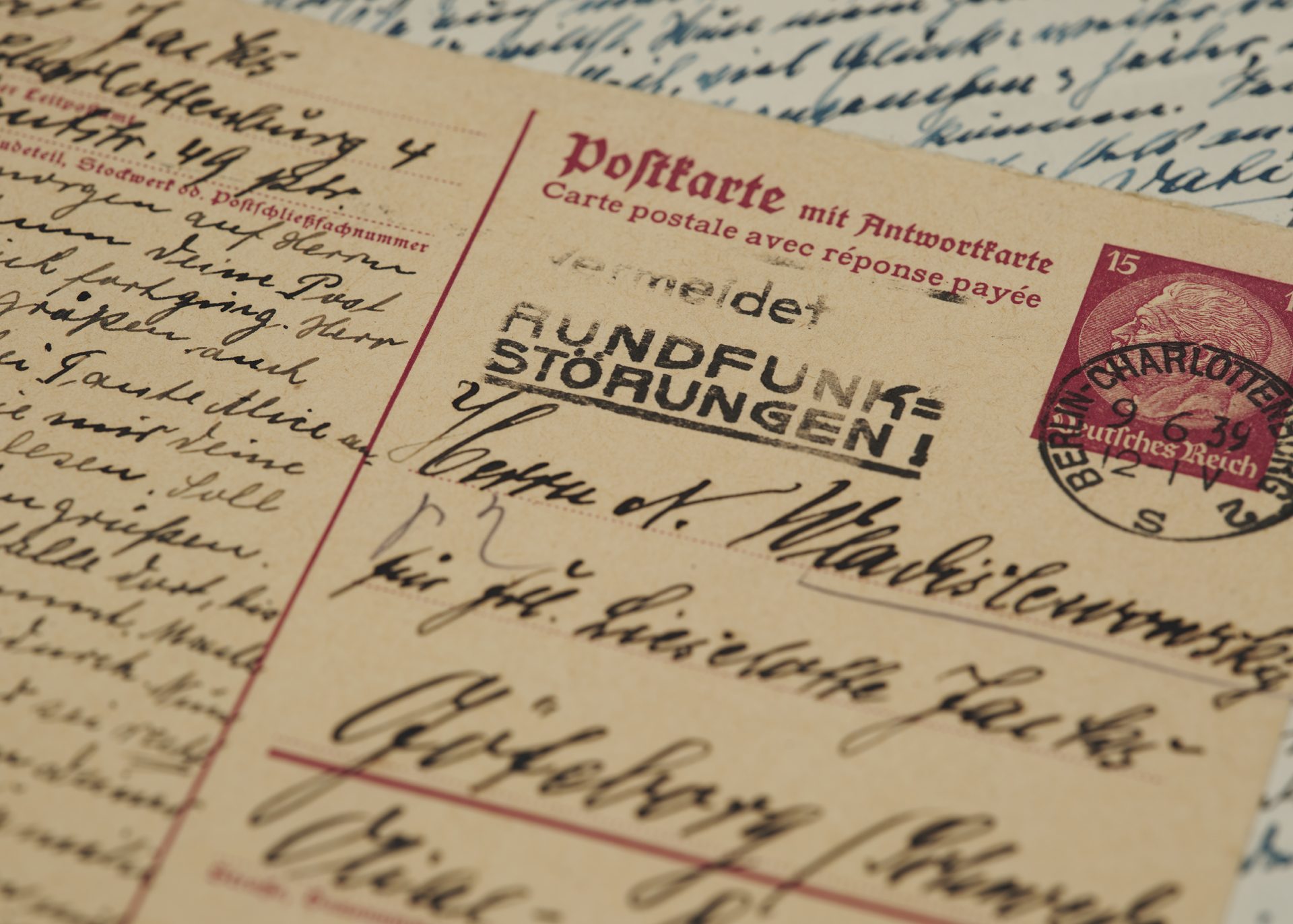

Lieselotte corresponded with her family in Nazi Germany for several years . In her first postcard to Lieselotte, postmarked 9 June 1939, her mother writes:

“I have waited for Herr Wiener every morning to read your post before leaving. Herr Wiener sends his regards, as does Mrs. Viktor. I visited Aunt Alice and read your card to dear Goldi. Greetings from your nearest and dearest also. Ilse’s things can stay where they are until someone comes for them. Don’t incur any expenses on that matter. Enough for today, my dear child. Heartfelt greetings and kisses from your loving mother. Give my regards to the W family and acquaintances. We have calmed ourselves now.’”

In a letter written in 1943, Aunt Rosalie writes:

“My dearest Lilochen.

I am pleased to tell you that I am healthy and feeling well. (…) Have you any news from your parents? Please write to me soon and warm greetings and kisses from your grandmother, who loves you.

Rosalie Jacks.”

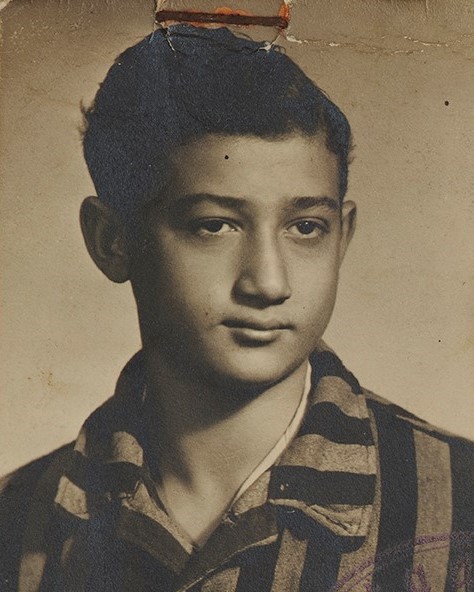

Gertrud and Alfred Jacks

Lilo's parents, Gertrud and Alfred, remained in Nazi Germany and did not survive the Holocaust. They were deported from Berlin to Auschwitz-Birkenau in the autumn of 1942 by Transport 23.

Rosalie Jacks

Lilo's grandmother Rosalie Jacks was deported from Berlin to Theresienstadt in Czecho-slovakia in December 1942 by Transport I/80. In the spring of 1944, Rosalie was taken from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz-Birkenau by Transport Ea. Rosalie did not survive the Holocaust.

Lilo's story

Lilo lived the rest of her life in Sweden. Lilo's son Greger has told the story of his mother and has donated objects, documents and photographs to the Swedish Holocaust Museum.

Header photo: Detail of Lieselotte's saved documents. Photo: Ola Myrin, Swedish Holocaust Museum/SHM.

Source:

- The museum’s collection. On the journey to Sweden, Lieselotte carried a small suitcase, a photograph and her passport. She saved these until she died. The letter was donated to the museum by her family and is now in our collection.

- Rudberg, Pontus. 2017. The Swedish Jews and the Holocaust. London: Routledge.

- Lomfors, Ingrid. 1996. Förlorad barndom – återvunnet liv. De judiska flyktingbarnen från Nazityskland. [Lost Childhood, Reclaimed Life: Jewish Refugee Children from Nazi Germany]. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.