The Lost Voices – Echoes of the Rescued of 1945 project includes about sixty Holocaust survivors who died shortly after arriving in Sweden. They came to be known as “the Rescued of 1945” and were buried at the Northern Jewish Cemetery – Norra judiska begravningsplatsen – in Stockholm. In total, up to 300 of the "1945 rescued" died as a result of their injuries, in various places around Sweden. They were buried as far as possible in Jewish cemeteries, such as in Malmö, Gothenburg, Karlstad and Norrköping, but also in other cemeteries, such as in Örebro and Lärbro on Gotland.

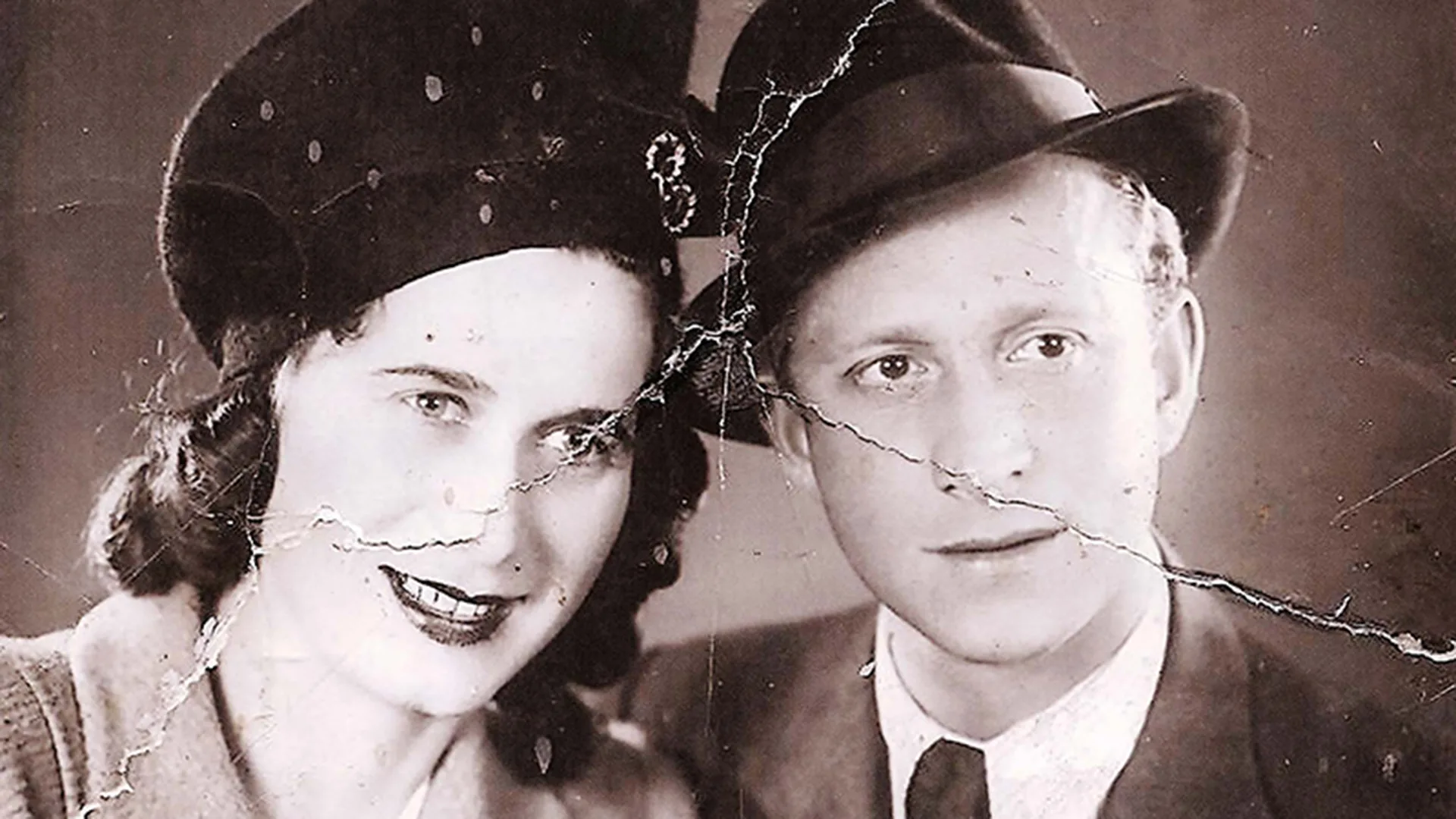

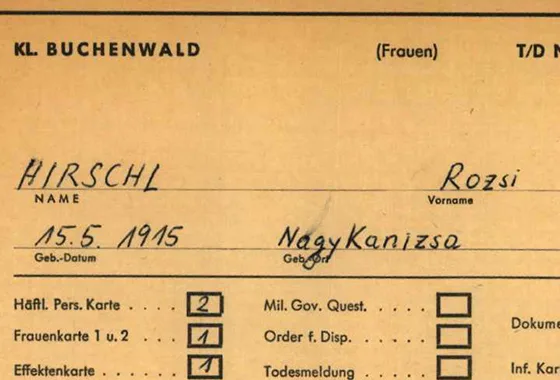

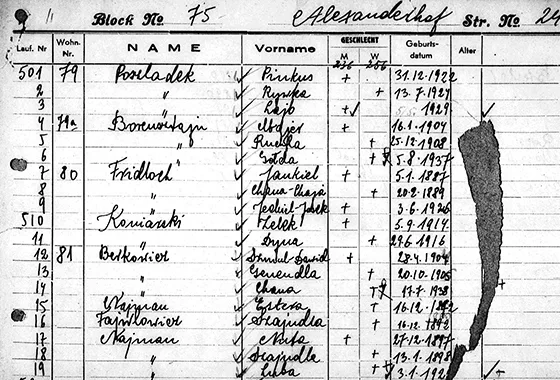

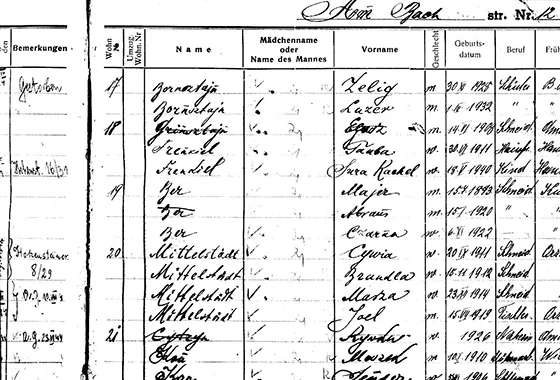

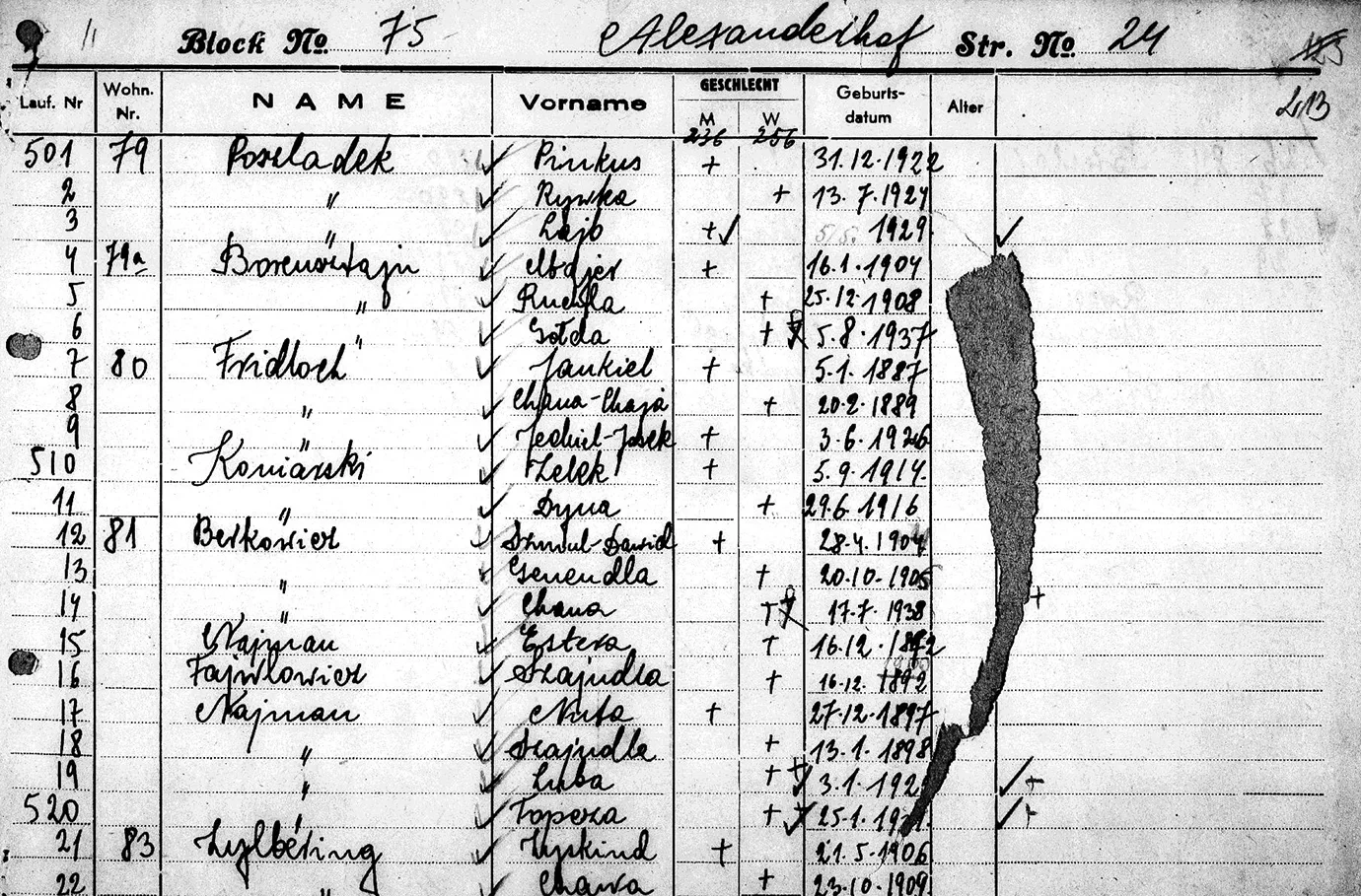

The project is led by Daniel Leviathan, a doctoral student in Jewish Studies, and the material is published in collaboration with the Swedish Holocaust Museum. This is an ongoing project that will be published in stages. We tell the story of ten survivors initially, including Rywka Posladek and Rozsi Hirschl. Rywka was just 14 years old when war broke out in 1939 and her home town of Łódź, Poland, was occupied by the Nazis. Rozsi had just given birth to Edit, her first daughter, and was living with her husband in Budapest when the Holocaust reached Hungary in 1944.

Their voices are forever lost to us, but their memory lives on. We are keeping their memory alive by telling their stories. The memory of who they were, where they came from and what happened to them. The memory of people, most of them young, from different backgrounds, different places, who all suffered Nazi atrocities simply because they were Jewish.

Sweden conducted a series of rescue and evacuation operations in the spring and summer of 1945, towards the end of the Second World War and shortly thereafter, bringing Jewish Holocaust survivors to Sweden. The most famous of these is the major Swedish Red Cross operation known as the White Buses, led by Folke Bernadotte. Between March and May 1945, this humanitarian operation saved thousands of people from Nazi prison camps, including Jewish prisoners.

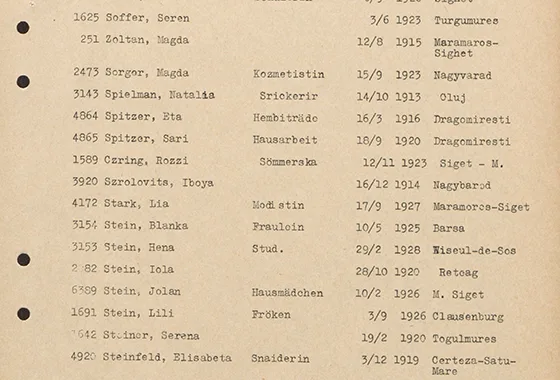

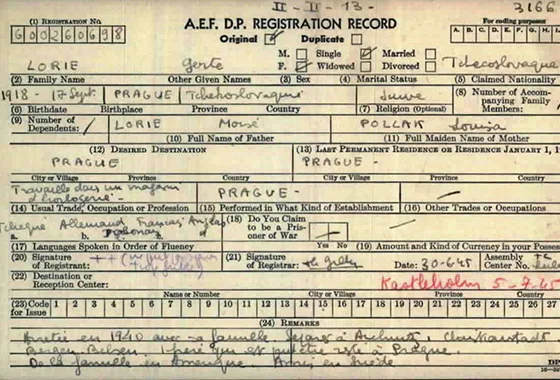

Shortly after the White Buses operation came to an end, Sweden – at the request of the allied refugee organisation known as the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) – accepted over 9,000 “displaced persons”, survivors from the former concentration camps. They came to Sweden to receive treatment so that they could be repatriated – return to their home countries – over time. The people who came to Sweden were referred to by the Swedish authorities as “repatriandi”, and by the Jewish communities as “the Rescued of 1945”.

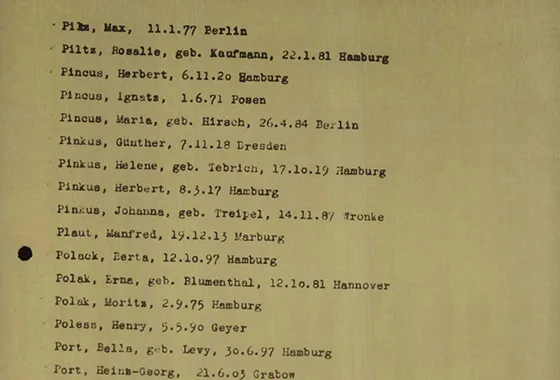

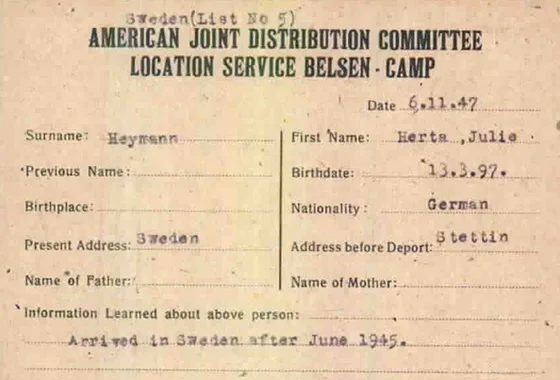

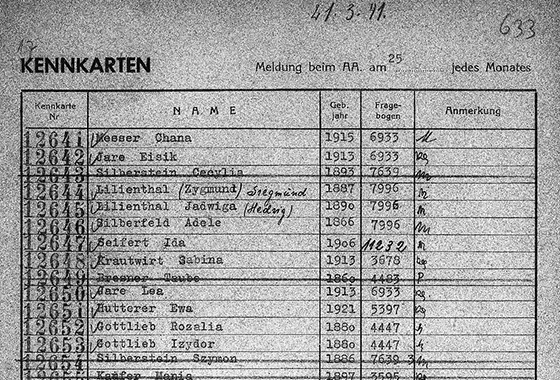

Most of the people who came to Sweden were Jews, mainly young women, from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. This is the camp to which the Nazis had been transporting prisoners towards the end of the war, often via the death marches from other concentration camps such as Auschwitz as the Allies approached. When Bergen-Belsen was liberated by the British on April 15, 1945, it held almost 60,000 prisoners and almost 13,000 unburied human bodies. After the camp was liberated, an assembly camp was established nearby for almost 30,000 former prisoners from various concentration camps. The survivors of the concentration camps often suffered from severe hunger and malnutrition, and Bergen-Belsen was struck by massive epidemics of TBC, typhoid, diphtheria and dysentery that killed almost 35,000 people in the spring of 1945, both before and after the liberation.

Top photo: Rozsi and Laszlo Hirschl. Photo: Yad Vashem.

Reception in Sverige

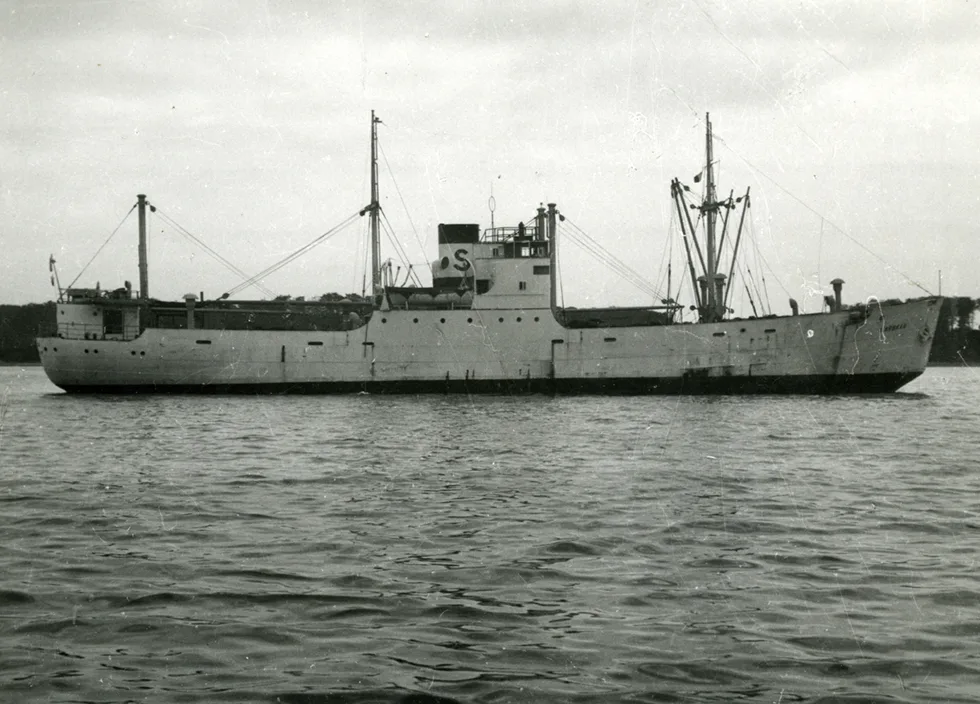

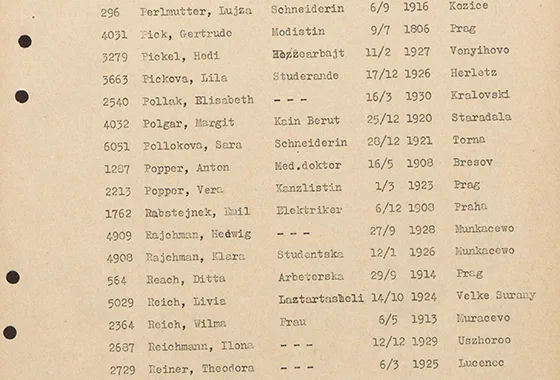

Over 9,000 people were brought to Sweden from Bergen-Belsen. Most of them were Jews from Poland, Hungary, Romania and Czechoslovakia, and many were seriously ill.

In Sweden, preparations to receive “the Rescued of 1945” were made by establishing a number of emergency hospitals, including one in Sigtuna, to receive the people arriving at Frihamnen in Stockholm. When the first survivors arrived at the port, however, some of them were so ill that they were unable to be transported to Sigtuna, and had to be admitted to the isolation hospital in Roslagstull. There, just a few kilometres from the port, the first of the people liberated from the camps died just a few days after arriving in Sweden.

They would not be the last to die from the harm caused by the Nazis and the Holocaust. In the months and years that followed, more than 60 Holocaust survivors in Sweden died as a result of their severe injuries. And they continued to do so into the 1950s and, in some cases, beyond that. Who were they? Where did they come from? What had happened to them and their families?

Archival material and photographs

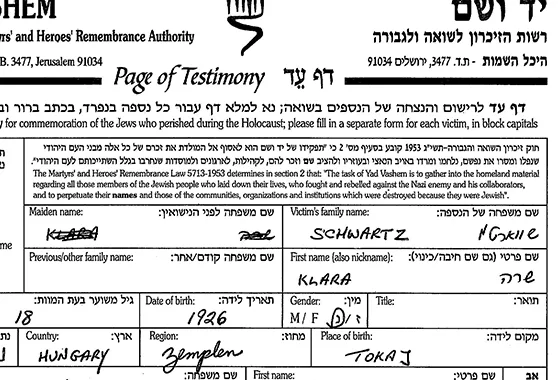

Not only was the Holocaust the actual murder of six million Jews, but also an attempt to completely wipe out all traces that these people had ever existed. Many of the survivors have made their voices heard, describing what happened during the Holocaust, but what about the people who never had the opportunity to make their voices heard, the people whose voices are lost?

Jewish Names

For centuries, Jewish people have taken names with origins in Jewish sources – the Hebrew Bible and Talmud in particular, names such as Abraham, David, Sarah or Esther. Over time, names from beyond the community have been taken – often with a Jewish twist.

Reference list

About the project Lost Voices

The project was initiated by the Jewish Community of Stockholm and has been realized by Daniel Leviathan, archaeologist and PhD student in Judaic studies, who himself carries the memories of his many relatives who were murdered during the Holocaust. The texts are produced by Daniel Leviathan and the material is published in colllaboration with the Swedish Holocaust Museum. This is an ongoing project that will be published in stages.

The project has been realized and carried out thanks to the 2021 scholarship from Micael Bindefeld´s Foundation in memory of the Holocaust. Thanks to the scholarship, we can now make visible the life stories of those who came to Sweden in 1945 but did not survive the injuries from the Holocaust.

The project has also recieved support from the Swedish National Heritage Board, the City of Stockholm, Eduard and Sophie Heckschers Foundation, Yad Vashem, the Clas Groschinskys Memorial Foundation, Robert Molander, Siv Finkelstein and Adele Fajntuch. The work has been carried out with the help of Anna Nachman and the Jewish Community of Stockholm, Hanna Nir, the Living History Forum, the Jewish Museum in Stockholm, and the Association of Holocaust Survivors in Sweden.